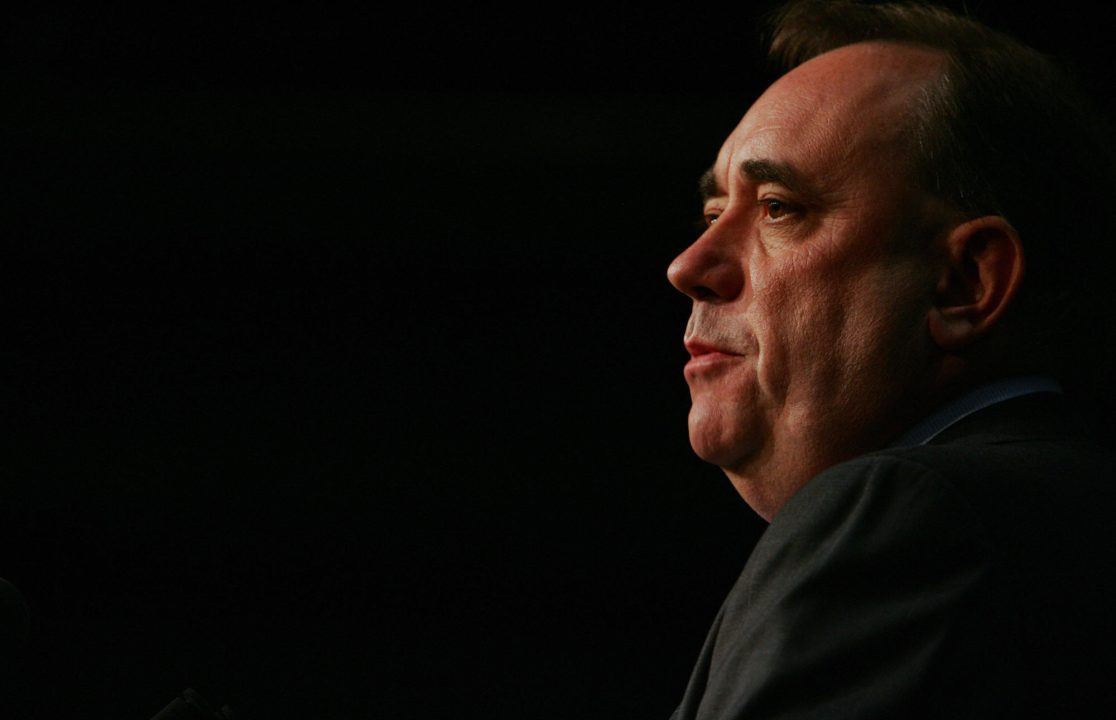

In the history of modern Scottish nationalism, Alex Salmond stands tallest.

Twice leader of the SNP, it was Salmond who took the party from the political and electoral fringe to mainstream player and eventually to government.

In the process, he led the Yes movement in the 2014 independence referendum, coming within ten percentage points of busting the 300-year-old Union.

Watch

Archive: Alex Salmond on STV’s ‘My Life In Ten Picures’

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA ferocious debater with a keen mind and quick turn of phrase, he had a master chess player’s skill for strategy and tactics. All were deployed in a near fifty-year career that made him one of the most significant figures of recent times.

After his resignation as First Minister, and with an enviable legacy to show for his efforts, Salmond made a number of questionable decisions that tarnished his legacy.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHe stood trial at the High Court on a number of alleged sexual offences and subsequently had to battle in the court of public opinion to rescue his reputation, which was in part saved by the decision of a jury to acquit him of all of the charges made against him.

The fallout from the way the Scottish Government handled the allegations of misconduct against Salmond led to a rift and then an irreparable falling out with his successor, Nicola Sturgeon.

It also made his membership of the SNP untenable. Rather than depart the stage for a relaxed retirement, Salmond continued to cast a shadow over his former party – and Sturgeon in particular.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHe became leader of the Alba Party. It gave him a platform to influence the debate on independence, but truth be told, he was very much a marginal figure who by then operated on the fringe.

Alexander Elliot Anderson Salmond was born in the West Lothian town of Linlithgow on 31st of December 31, 1954, the second of four children, born to Robert and Mary Salmond.

Watch

Scottish independence: Ten years on since historic 2014 referendum

His father had been a Labour man up until the West Lothian by-election of 1962, when he switched allegiance to the SNP. His mother, a dainty and very dignified lady, had Conservative sympathies, which changed as her son started to make his mark in life.

His grandfather sparked an interest in Scottish history. At the University of St Andrews he became a committed nationalist although he once voted Labour in a local by-election that the SNP did not contest.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAfter graduating in economics and medieval history in 1978, he entered the Government Economic Service, before moving on to the Royal Bank of Scotland in 1980, working as an oil economist.

The “Scottish Assembly” debates of the 1970s raged as the young Salmond crystallised his beliefs.

He viewed his support for independence as a stepping-stone to a more socially just Scotland. In pursuit of this, he believed in a big tent approach to delivering his cherished goal.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSNP support at the October 1974 General Election delivered 11 MPs, elected on a third of the popular vote.

That support collapsed in 1979 and Salmond was one of those who took the view the party needed a left-of- centre political identity, to help anchor it and insulate it against being seen as just a protest vote.

He joined the Left Wing 79 Group, but was expelled from the party for his efforts to agitate for change, later being readmitted when internal groups disbanded.

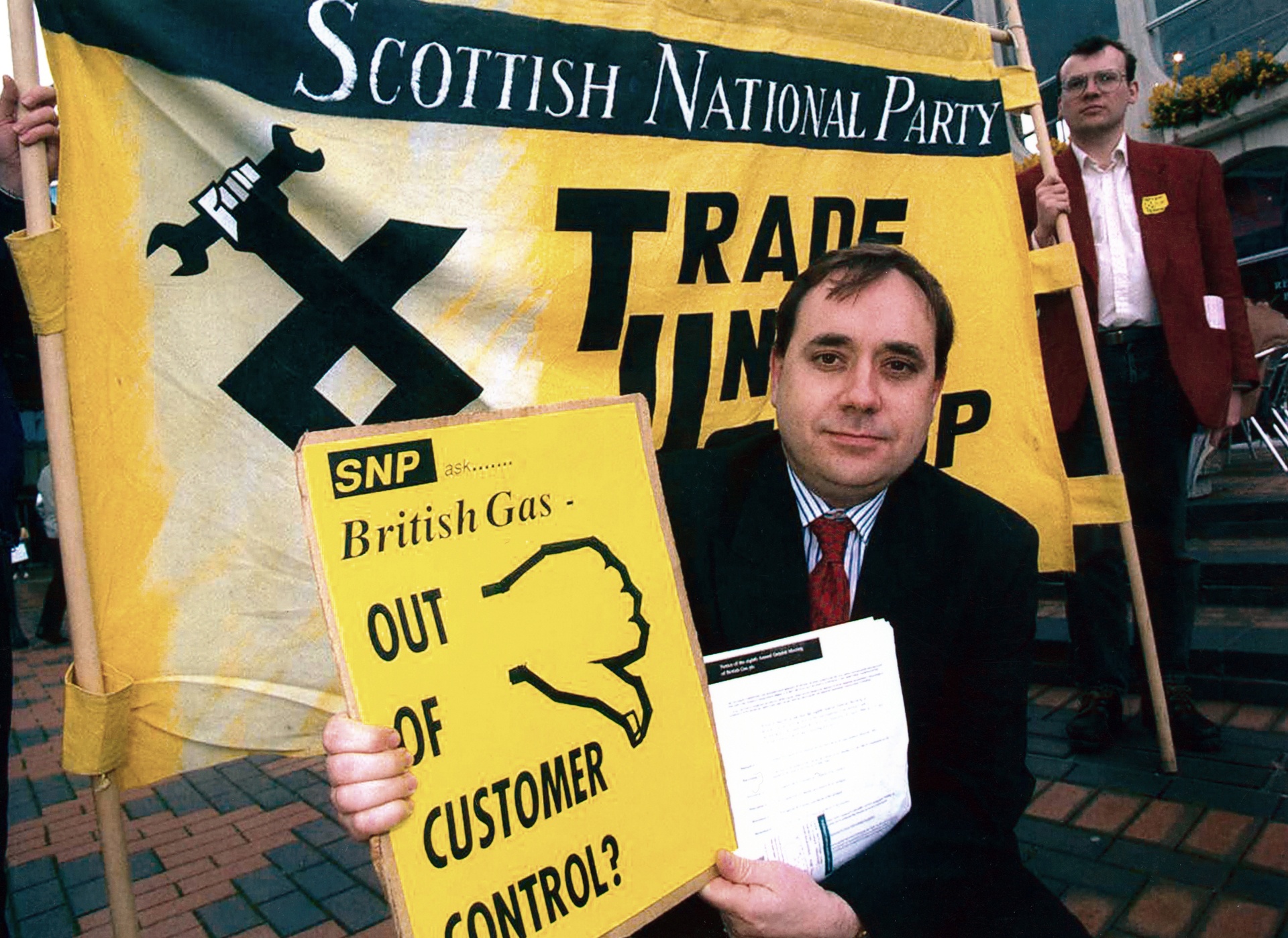

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHe was elected as the Member of Parliament for Banff and Buchan in 1987 and he quickly made a name for himself, disrupting Chancellor Nigel Lawson’s budget in 1988. By now, he was the party’s deputy leader.

He was a commanding presence on television and a sharp debater in the parliamentary chamber even if his platform speeches lacked rhetorical flair.

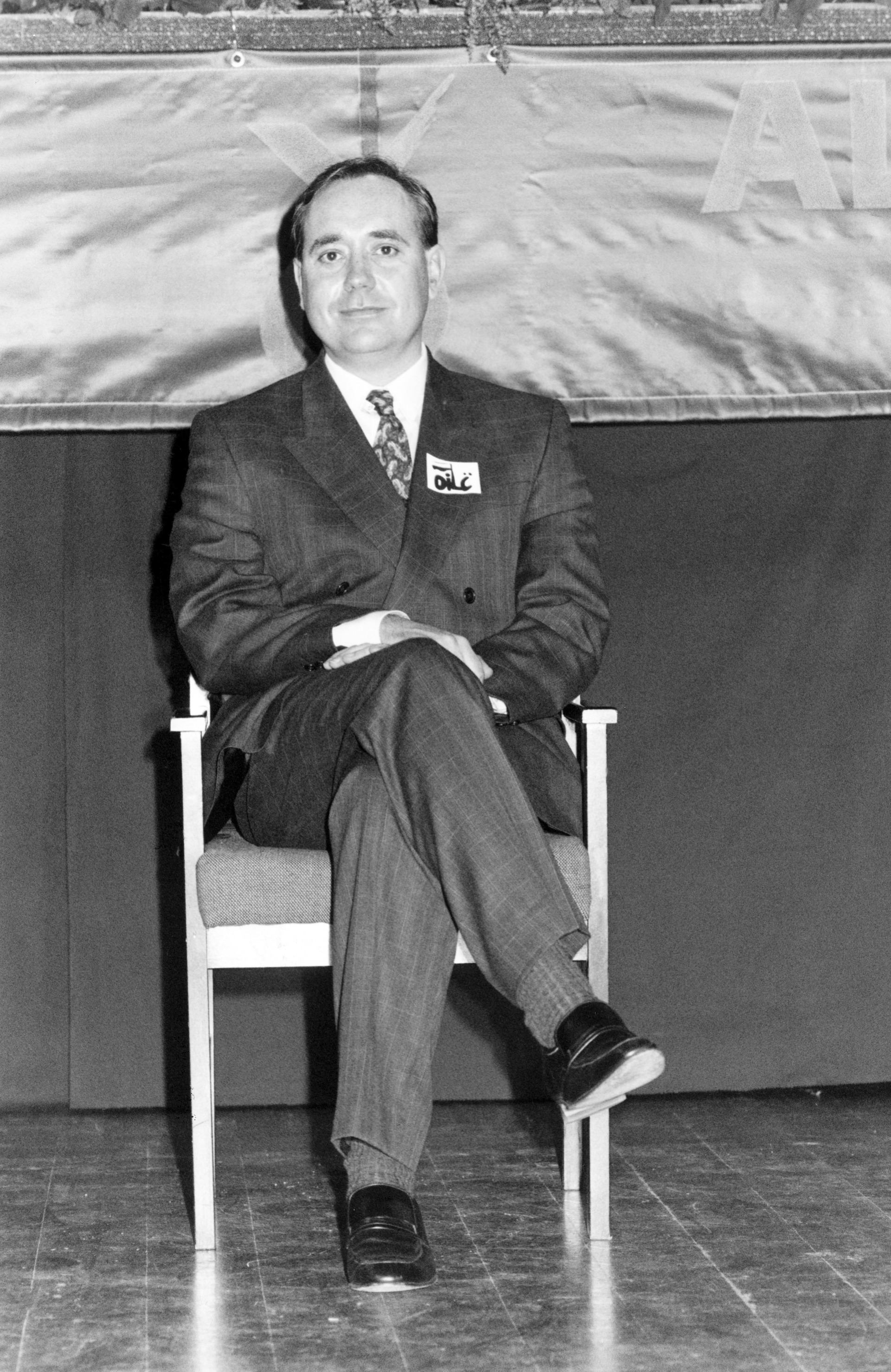

When Gordon Wilson stepped down as SNP Leader in 1990, the party establishment backed Margaret Ewing. Ewing was a lovely woman, popular across the political parties and who was the most traditional of nationalists.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAlthough bright and capable of eloquence, she simply did not possess Salmond’s intellect or campaigning zeal.

With the help of the Young Scottish nationalists, Salmond emerged victorious and quickly set about moulding the party to mirror his own politics.

Prior to winning the leadership, he was out-manouvered by Gordon Wilson and Jim Sillars on the issue of joining the constitutional convention. Sillars also cleverly endowed Salmond with the “Free by 93” strategy for the 1992 General Election.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSalmond thought the strategy was nuts although he refused to assert his authority by binning it, in case he split the party.

He led the SNP to retain their three seats on 21.5% of the vote, up 7% on the 1987 level of support. He then quickly worked to define the party in social democratic terms. Salmond would refer to the need for the SNP to own up to an ideology.

The decision to embrace social democracy is an under discussed change in the history of the SNP. The decision would result in Labour voters feeling comfortable to switch their allegiance years later.

Getty Images

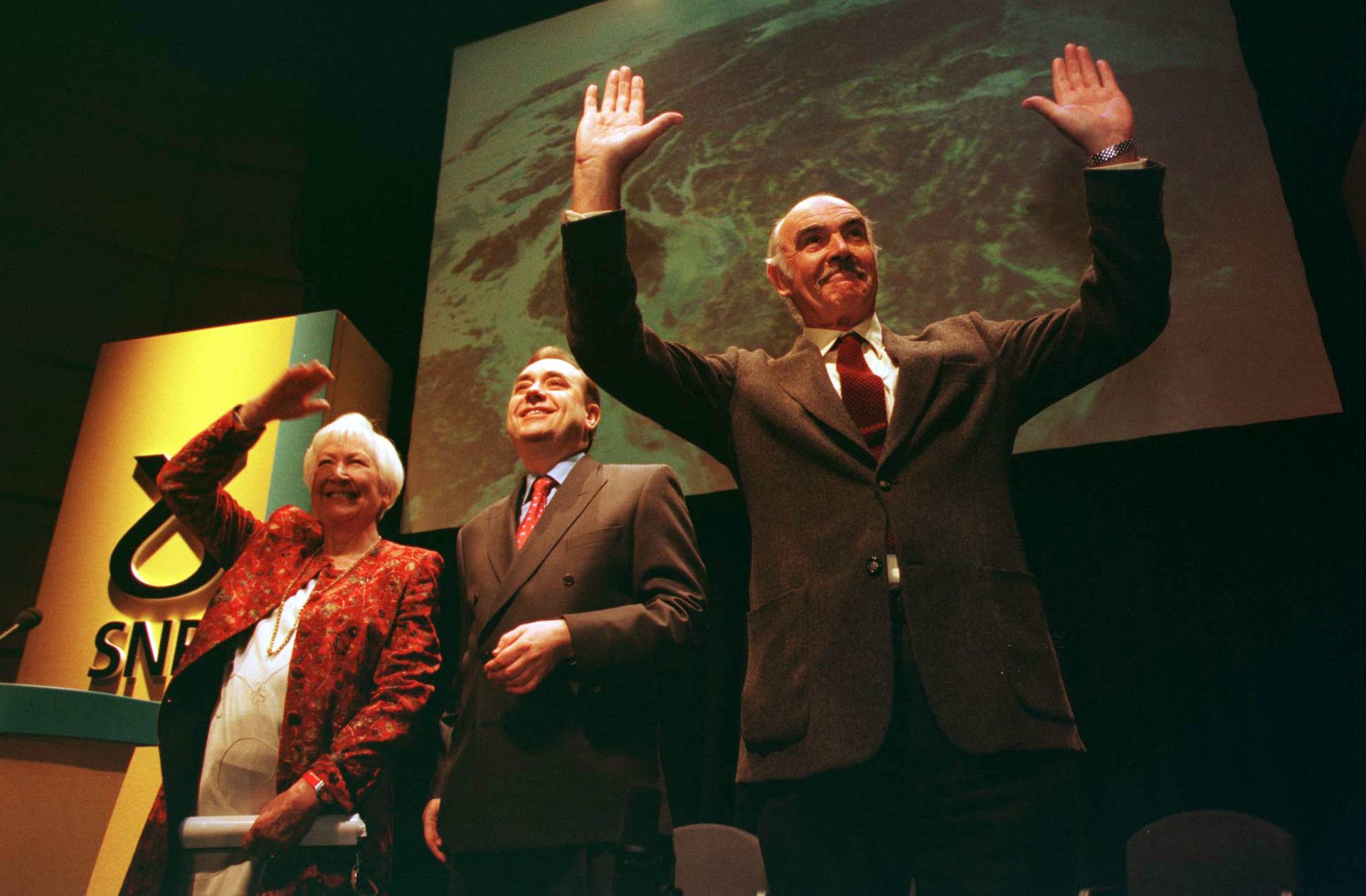

Getty ImagesWith the election of New Labour in 1997, Salmond worked hand in glove with Labour’s secretary of state for Scotland, Donald Dewar, first to secure a victory for the “Yes, Yes” movement in the 1997 devolution referendum and then delivering the subsequent legislation onto the statute book.

Salmond rated Dewar but the feeling was not mutual in part due to Dewar’s occasional bent for small mindedness.

As the election to the first Scottish Parliament took place in 1999, Salmond cemented his reputation as a risk taker. He proposed a “penny for Scotland” tax rise for education and, as the campaign started, condemned NATO intervention in Serbia – describing it as an act of “dubious legality and unpardonable folly”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor much of the 99 campaign the SNP were on the backfoot. Given they were competing to govern, scrutiny was intense, particularly in relation to Scotland’s fiscal position in relation to the rest of the UK.

The party emerged with a credible 35 seats seats on 29% of the vote, giving a firm base on which to make a more meaningful challenge.

Then, one year into the Parliament, Salmond stunned politics by quitting as leader. The party then fell back at the 2003 elections under John Swinney’s leadership. Swinney quit and Salmond would win the leadership for a second time despite repeatedly insisting that he would not run.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHaving quit Holyrood to lead at Westminster, he won election back to Holyrood in 2007, winning Gordon with a majority of 2,062.

More importantly however, the SNP won their first national election in Scotland, claiming 47 seats against 46 for Labour. Scottish politics changed fundamentally.

He dealt with the 2007 terror attacks on Glasgow airport with great skill and his administration was marked by policies that abolished tuition fees and froze the council tax. The office of First Minister appeared to benefit from his obvious gravitas, and it helped cement the idea that the SNP were a party who belonged in government.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThen in 2011, the nationalists achieved what was thought to be near impossible. They won an outright majority of seats in the 129-seat Scottish Parliament.

The fourth term of Holyrood was dominated by the independence referendum, which would eventually come on September 18, 2014.

Salmond fought a positive campaign that caught the mood among many undecided voters. The Yes movement continued to advance even although Salmond lost the first TV debate to Alistair Darling who led the Better Together campaign.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe economic case for independence came under intense scrutiny and Salmond rolled with the punches while trying to remain upbeat about the possibility of victory.

When the first declaration came from Clackmannanshire in the early hours of September 19, Salmond knew the game was up. The pro-Union side won by 55% to 45% with an eleventh hour offer of more devolved powers, doing enough to deliver victory.

Salmond resigned that day, declaring “my time as Leader is nearly over, but for Scotland, the campaign continues and the dream shall never die”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSalmond returned to Westminster in 2015.

In some respects, he seemed more at home in the Commons than at Holyrood. The bigger stage appeared to appeal. Salmond was also a man who liked the trappings of importance – good restaurants, chauffeurs etcetera – and this was more readily available in London than in Edinburgh.

He lost his Gordon seat in 2017. In his 60s at this point, retirement was an option but not one he considered seriously.

It was around this time that his judgement came into question. Indeed, some colleagues were scathing of him in private. He hosted a show on the RT Channel (formerly Russia Today).

In 2018, he resigned from the SNP when allegations of sexual misconduct emerged. He successfully took the Scottish Government to court to prove the way civil servants handled complaints against him was tainted with bias.

His supporters believed that a cabal close to Sturgeon orchestrated a campaign to get him.

In 2019, in a move that left seasoned observers flabbergasted, he was charged with 14 offences including two counts of attempted rape. He was acquitted of all charges in March of 2020 after a two-week trial.

Although acquitted, the pre-trial publicity and embarrassing evidence about his behaviour, battered his reputation.

In March of 2021 he joined and then led the Alba Party but they performed miserably at the 2021 Scottish elections.

Salmond cut a forlorn figure at the count in Aberdeen. It was hard to believe that as he wandered around the count centre that he had once almost delivered a constitutional revolution.

The former Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson (whom Salmond admired enormously), once said that he wanted to make his party, the natural party of government. One aspect of Salmond’s legacy is that he created the conditions that ensured that is what the SNP became in Scotland.

A natural leader who lived and breathed politics, he used all of his talents to achieve high office and become an enduring public figure, one of genuine historical note.

His personality foibles – a tendency to bully, a certain vanity and a love of the finer things in life, undoubtedly narrowed the range of those whose love for him was unconditional.

For all that, he is one of the most significant figures of the last half-century.

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country