Westminster returns from the summer recess on Monday.

The parties are now gearing up for the push ahead of a general election that will definitely come next year. The only question is whether the Prime Minister goes early in 2024 or opts for a late election.

There is a mood of resignation on the Tory benches. By-election losses act as a near permanent reminder that the mood of voters is for change.

Many Tory MPs have chosen to stand down. The cost-of-living crisis continues to tighten an electoral noose, as the government searches frantically for a narrative in an attempt to turn the electoral calculus on its head.

The problem for Rishi Sunak is quite simple. The squeeze on household budgets will be with us for some time and it is unlikely that voters will feel any less pain by the time the election is called.

Inflation remains stubbornly high. Interest rates will be higher for longer as the Bank of England’s monetary policy committee plays catch up on its own failures to reduce the rate at which prices are rising.

The quantitative easing spurge that has led to an injection of cheap money into the economy is at an end. The government now finds there is no fiscal room for manoeuvre as households and business continue to battle with rising prices.

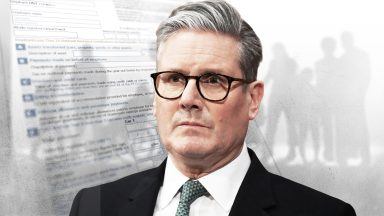

Some Conservatives hope that as an election gets closer and the stakes become real, voters will take a closer look at what Sir Keir Starmer is offering. Or not, as the case may be.

The charge from the government is that the opposition stands for very little apart from not being the Tories; that they are an alternative government but without a plan.

It is true that Starmer has taken caution to a level that means he spends a lot of interview time saying very little.

For many traditional Labour voters, there are fair questions to ask: Where are the red lines? What are the policies that are non- negotiable?

Abolition of the rape clause and the two-child benefit cap? Clear pledges on spending? A progressive tax policy?

It is one thing for an opposition to wait until nearer the election before it makes firm commitments, but it is quite another to hedge your bets on issues that should be clear-cut in terms of taking a stand.

Starmer, a Remainer at the EU referendum, has simply accepted Brexit. Again, this is perhaps more to do with shutting down an issue that could provide the Tories with an electoral fillip, but it sustains the view that he is taking stances – not out of principle but out of expediency.

Internally, he is brutal in dealing with people on the Left he deems a roadblock to power, and the recent chumminess with Tony Blair has the Left in despair. The fear is that should they win, Labour will govern in a way that does not redistribute wealth or power.

So long as Labour’s poll ratings and by-election performances remain strong, there is no incentive for Starmer to be more specific about what a Labour government will do. But he will know that such lightness in policy terms will not survive an election campaign. His tactic of saying very little is on borrowed time.

Starmer and Humza Yousaf face a challenge at the upcoming by-election in Rutherglen and Hamilton West. Both need a victory for different reasons.

If Labour cannot win the by-election, then electoral life for Starmer come the UK general election becomes a whole lot more difficult. He desperately needs a victory to be made in Scotland, as well as England and Wales.

But the nature of any Labour victory in Rutherglen is also important. If Labour knocks the SNP on the basis of tactical transfers from the Conservatives, then any victory has to come with a health warning.

A victory based on tactical voting and not a straight transfer from the SNP to Labour would lead to significant qualification being put on what a victory will mean come the general election.

Unless the SNP vote is falling too, Rutherglen may signal a modest revival for Labour, rather than be a portent of a significant collapse in nationalist representation at Westminster.

If a Labour victory raises the possibility of a widespread assault on SNP seats in the central belt, then Yousaf will come under considerable pressure to turn matters around in the run-up to a general election.

His chief worry is that defeat in Rutherglen signals an end to the electoral dominance of his party and that a narrative takes hold that they are in retreat.

By-elections are snapshots of opinion and very often they are useless barometers in measuring what will happen at a general election.

This by-election could be different for several reasons. First, it is not being held in midterm but, in all likelihood, a year out from an election.

Second, it could say something significant about the electoral dynamics between Labour and the SNP in a way that Rutherglen echoes all the way to the next general election.

The stakes are high. What happens in this constituency next month could very much affect what happens in Scotland as a whole next year.

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country