Nicola Sturgeon is now Scotland’s longest-serving First Minister, the fifth person to hold the post.

Her path to the top was born in the defeat of the independence referendum in September 2014.

Alex Salmond quit when the people spoke and said “no” in a constitutional plebiscite which saw unprecedented levels of voter engagement.

In that time, the SNP has become all-conquering as an electoral force. Sturgeon exercises a hold on her party and the Government, arguably greater than that of her predecessor.

She has benefitted from Scottish politics being redefined by the prism of the constitution.

That means, whatever reservations some voters may have about the SNP’s record in government, they back the party as a means of keeping the independence dream alive.

The Tories have benefitted from this dynamic too, as more hardline Unionist voters embrace the tougher line they take on demands for a second referendum.

For those who pine for a politics dominated by traditional policy concerns, this constitutional vortex, spun more violently by Brexit, is a disaster, since they believe the Government is given a get-out-of-jail-free card for failures on more basic voter concerns.

The opposition case is simple: the SNP’s record is appalling.

Closing the attainment gap in education is a fail, they contend. The charge sheet also reads:

- Hospital waiting times going badly in the wrong direction even before Covid;

- Procurement of ferries, schools and hospitals, a shambles on their watch with catastrophic consequences for the public purse;

- Record drugs deaths;

- A financial scandal at the Crown Office and a creaking court system.

In fact, the opposition ask, what goes right in Sturgeon’s Scotland?

Nicola Sturgeon’s approval ratings remain high. The Government’s supporters say she has continued to fund key policy gains for Scots not enjoyed south of the border, such as free tuition, personal nursing care and prescriptions.

New benefits, they argue, have attempted to help the poorest. They also say she projects the image of a tolerant, outward-looking nation, socially liberal and rights-based, and is a far cry from the narrowness of Brexit Britain.

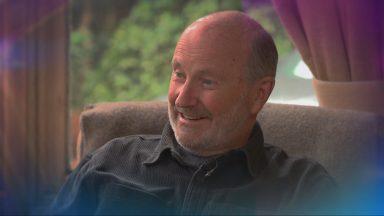

STV News

STV NewsVoters can look at the record and decide for themselves. What is clear is that the SNP enjoys impressive levels of support for a party that has now been in government for 15 years.

There have been two big tests of her personality in that time. The first relates to the meltdown in her relationship with her predecessor and mentor Alex Salmond. When harassment allegations surfaced about him, she tip-toed carefully in the ensuing furore before cutting him loose.

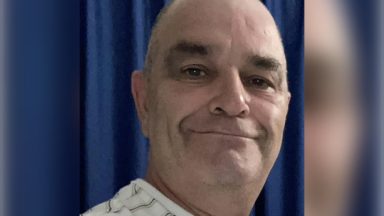

STV News

STV NewsInternal critics, and they do exist, are cagey about going on the record. They allege she is calculating and would throw any colleague under the bus in the self-preservation stakes.

Her supporters argue she is tough and demanding and detect a large amount of misogyny in the criticisms of her.

What is beyond argument is that she is a clear and effective communicator and a skilled debater. These attributes have been put to good test in her second leadership challenge, that of managing the pandemic.

Much of what went wrong has a common echo throughout the constituent nations of the United Kingdom, but it is unarguable the messages delivered each day from Edinburgh were clearer than the frequent chaos of briefings at Number 10.

Her formidable debating skills allow her to argue her way out of trouble when hit with scathing criticisms from the opposition leaders at FMQs. She can roll with the punches, deflect deftly and turn the tables. Opponents say, for all her skills, she cannot hide from a record of lamentable failure.

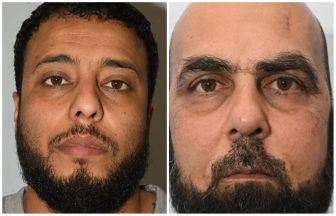

SNS Group

SNS GroupShe has played policy issues safely, as has been the want of every First Minster of the devolved era.

For a politician of the left, she has been somewhat conservative in her approach to governing and arguably her actions don’t synchronise with much of her rhetoric, particularly on the necessary actions to better the lot of the marginalised.

“Managerialism” is to be found in all the parties. That is to say, traditional ideologies have played second stage to governing pragmatically and often from the centre ground, where most electoral opinion is to be found.

Her legacy is yet to be written, in part because the defining issue of her career will be the delivery, or not, of a second independence referendum.

Some within the wider Yes movement despair of Sturgeon and see her as a barrier who takes an overly cautious and legalistic approach on the national question. They want agitation and the mobilising of extra parliamentary action in the arguments over national sovereignty.

Sturgeon would contend the one thing that will bury independence is half-baked strategies from half-baked minds, from people who can luxuriate from a position of not having to take responsibility for anything.

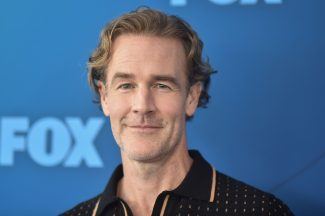

SNS Group

SNS GroupThe current stand-off between Sturgeon and Boris Johnson over IndyRef2 will continue. There is no obvious route for the First Minster to take, so she takes cautious steps aimed at politically marginalising Westminster in an effort to bolster the number of troops who have concluded that the UK is a busted flush in governance terms.

This issue may yet end up in the courts. It will be protracted. She will not be in a position to deliver it soon, if at all.

It is, however, above all else, the issue on which her legacy rests.

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country