The census figures are an essential tool in allowing policy makers to plan public services well into the future.

The trends in population growth inform a whole host of decisions.

How many schools and hospitals will be needed to service the needs of all citizens? What do the numbers in retirement mean for the social care sector? What do these population figures mean for the cost of certain policies like the free bus pass and free personal and nursing care?

I would suggest that the census findings should send alarm bells ringing in key government departments. Why?

Put simply, the population growth does not seem to me to be large enough to boost the tax take to underpin the challenges faced by public services to do ever more for a growing population of senior citizens.

Out of a total population of 5.4 million, just short of 1.1 million citizens are aged 65 and over.

That demographic is going to place a huge demand on the public purse by way of higher pension payments and the likelihood that as people live longer, NHS interventions will become more frequent placing yet more demand on a service many believe to be at breaking point.

Statisticians will be able to make quite firm predictions about the consequences for public spending of the trends identified by the census.

We know broadly what demands will be made in the future what we don’t know is how they will be paid for.

The orthodoxy among the main political parties is that economic growth is essential to expand revenues and pay for the greater demand for services.

Now for that to happen, you need more jobs and a skilled population capable of filling those jobs and it is here that there are some worrying trends.

Post-Covid many employers, particularly in the hospitality sector, simply cannot find workers.

Indeed, many employees in their mid-50s decided to hasten retirement plans. The pandemic led to a time for reflection among many older workers and some have decided to bail out of the labour market.

Now today’s figures show Scotland’s population grew by 2.7% since the previous census in 2011. But that rate of growth is smaller than in the previous decade. Between 2001 and 2011, the population grew by 233,000 or 4.7%.

These growth figures are lower than comparable figures for England and Northern Ireland. Indeed, if it were not for migration, Scotland’s population would have fallen by nearly 50,000.

In short, population growth is behind most of the rest of the UK. What modest growth there is is being charged by migration. Worryingly, it is unlikely to be growing at sufficient levels to give comfort to policy makers that the future tax take will put public services on an unarguably sustainable footing.

The debate around migration matters. Undoubtedly, in some local authority areas in England, demand for services is increasing at such a rate that there are legitimate questions about whether services can cope with the demand.

For some, the answer is to cut net migration and only encourage skilled workers to come to the UK.

Allied with a get-tough policy on the separate issue of asylum, some on the right believe that the system in the UK is broken and that our rules and benefits system acts as an incentive for the “wrong type” of migration.

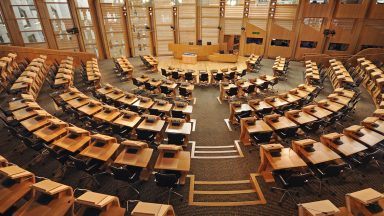

The problem for any Scottish Government which wants to head in a completely different direction on migration is that the key levers remain the preserve of Westminster.

The difference in both substance and tone between politicians at Holyrood and Westminster is stark on the various migration issues.

Scottish ministers believe that the “one size fits all” approach is positively harming the ability of the Scottish economy to grow, and they argue that responsibility for immigration matters should be devolved.

There is frankly, no sign of that happening, not now or in the future. How you grow the workforce on the basis of sluggish population growth is a huge challenge and it is a challenge for which there are no immediate answers.

The trends identified by the census should start a fundamental debate about the long-term sustainability of what we currently take for granted but I bet politicians will dodge the debate because they may have to embrace a degree of reality that will mean tough messages being sent to voters.

Longer term, they will be forced to do less because they won’t have the resources to do more and that will continue a narrative of “failing services”.

Inevitably services have to be aligned with what is affordable and in the absence of growth fuelled in part by a growing working population, it is difficult to see how our NHS in particular can possibly meet public expectations.

Ministers north of the border will no doubt take comfort from the fact that a study published on Thursday found around 60% of Scots feel that immigration is positive for Scotland.

Conducted by the Diffley Partnership, the research found that 59% described immigration as positive whilst only 18% thought it had a negative effect.

Director Mark Diffley, addressing the broader findings, said: “The survey shows that we feel broadly comfortable with and welcome migration to Scotland, with six in ten thinking that migration has had a positive impact on Scotland, although there is a minority of the public which views migration in a more negative way.”

There may be an appetite here for more migration, but the current devolution settlement frankly slams the door shut on a meaningful sea change in policy.

And in the absence of a material increase in the working population, it is difficult to see how the crisis stories around crumbling public services will come to an end anytime soon, if at all.

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country

iStock

iStock