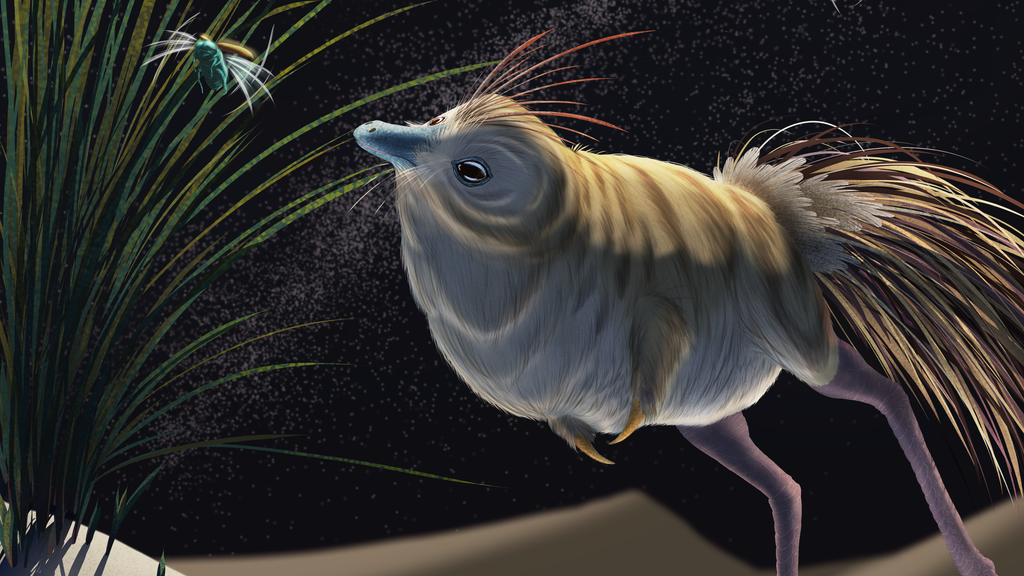

A tiny dinosaur that lived in the desert had extraordinary vision and owl-like hearing that enabled it to hunt in the dark, new research has found.

Scientists have long wondered whether theropod dinosaurs – the group that gave rise to modern birds – had sensory adaptations similar to those of birds which enable them to hunt prey at night.

A new study sought to investigate how the vision and hearing abilities of dinosaurs and birds compared and discovered that a theropod named Shuvuuia, part of a group known as alvarezsaurs, had both extraordinary hearing and night vision.

The international team of researchers used CT scanning and detailed measurements to collect information on the relative size of the eyes and inner ears of nearly 100 living bird and extinct dinosaur species.

Wits University/PA

Wits University/PAThe research follows pioneering work by Dr Stig Walsh, senior curator of vertebrate palaeobiology at National Museums Scotland (NMS), into the brains and senses of fossil birds, and used CT scans of the skulls of living bird species held in NMS collections.

Dr Walsh said: “I’m pleased to have been part of this important piece of research. Birds are the only surviving direct descendants of the dinosaurs, and so it makes sense to look at the characteristics of living birds today when we’re thinking about how different species of dinosaurs might have lived and adapted.

“In this case we’ve shown that, just like owls and other birds today, some dinosaurs would have been active and hunted at night, which is really interesting.

“The study also shows again the value of comprehensive natural history collections like the one we have here at National Museums Scotland.”

American Natural History Museum/PA

American Natural History Museum/PAShuvuuia was a small dinosaur, about the size of a chicken, and lived in the deserts of what is now Mongolia more than 65 million years ago.

To analyse hearing, the team measured the length of the lagena – the organ which processes incoming sound information which is called the cochlea in mammals.

The barn owl, which can hunt in complete darkness using hearing alone, has the proportionally longest lagena of any bird.

To assess vision, the team looked at the scleral ring, a series of bones surrounding the pupil, of each species. Like a camera lens, the larger the pupil can open, the more light can get in, enabling better vision at night.

By measuring the diameter of the ring, the scientists could tell how much light the eye can gather.

The team found many carnivorous theropods such as Tyrannosaurus and Dromaeosaurus had vision optimized for the daytime, and better-than-average hearing presumably to help them hunt.

However they discovered Shuvuuia had an extremely large lagena, almost identical in relative size to today’s barn owl, suggesting it could have hunted in complete darkness.

The study, published in the journal Science, was led by Professor Jonah Choiniere of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Dr James Neenan, the joint first author of the study, said: “As I was digitally reconstructing the Shuvuuia skull, I couldn’t believe the lagena size. I called Prof Choiniere to have a look.

“We both thought it might be a mistake, so I processed the other ear – only then did we realise what a cool discovery we had on our hands.

“I couldn’t believe what I was seeing when I got there – dinosaur ears weren’t supposed to look like that.”

With the new data on Shuvuuia’s senses, the scientific team believes it would have foraged at night.

The University of Oxford, the American Museum of Natural History and George Washington University were also involved in the study.

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country

PA Wire

PA Wire