Kilts, tartan, shortbread, whisky and bagpipes are among some of the things that make up the stereotype of Scotland.

They can also be found in large quantities and in various combinations in tourist gift shops across the country.

Haggis falls among these objects that many consider intrinsically linked with Scotland.

But the sausage-like food, stuffed with a mixture of sheep offal, onion, oatmeal, suet and spices, was not always thought of as distinctly Scottish.

Joy Fraser, adjunct professor in the department of folklore at Memorial University in Canada, has co-authored research about the cultural significance of the Scottish national dish and what it says about the relationship between Scotland and England.

“There was definitely a dish called haggis or haggis pudding that was known in England since at least the 13th century”, she told STV News.

“There was nothing seen as particularly Scottish about it.”

In the 1600s, recipes for haggis begin to appear and show that it was a luxurious dish, Dr Fraser said.

“In the 1700s, it’s pretty clear that it’s wealthy households in Scotland that are mostly eating this dish”

Dr Joy Fraser

“There were quite expensive ingredients like spices in the dish as well. So it was pretty much a delicacy at the time.”

There was not such a strong distinction between savoury and sweet meaning many recipes called for cream, eggs, sugar, rosewater, dates and currants to create something more akin to a pudding.

“In the 1700s, it’s pretty clear that it’s wealthy households in Scotland that are mostly eating this dish, but then you’ve got increasing tensions between the Scots and then English in the wake of the Union of Parliaments”, Dr Fraser explained.

The formation of the union is followed by the Jacobite rising in 1745. Anti-Scottish sentiment flared up south of the border at the same time as Scots moved to London and take up influential positions in the British state.

National Trust for Scotland

National Trust for Scotland“There’s a lot more contact between Scotland and England that means that Scots become familiar enough to caricature.”

It is around this time that haggis becomes part of a cluster of stereotypes contributing to ideas and attitudes about Scots and what it means to be Scottish.

“There’s the figure of the beggarly Scot who appears in a lot of English satire during this period,” Dr Fraser said.

Cartoons depicted Scots in poverty and squalor building an image that presents haggis as a food “not really fit for human consumption”.

iStock

iStockIn reality, it remained a dish consumed on special occasions rather than a staple of the everyday lower classes – the ingredients were not cheap and it was complicated to prepare.

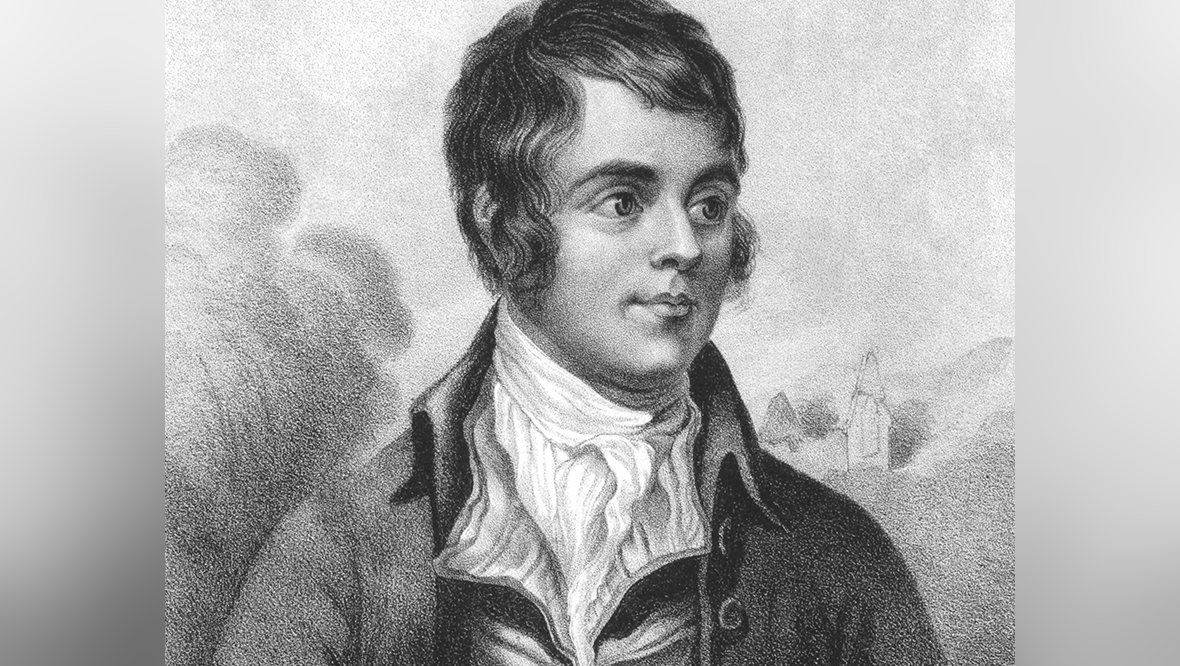

Then, in 1787, Robert Burns published his Address To a Haggis, changing how Scots viewed the food completely.

“Burns is kind of overturning that negative pejorative stereotype that had been constructed within English popular culture,” Dr Fraser said.

In the poem, the bard creates an idealised image of Scottish rural life with the rustic lead returning home to his little cottage from a day of work in the field to a humble yet hearty meal of haggis with his family.

“This becomes part of this whole sort of idealised image of the Scots as kind of resourceful, resilient and independent”

Dr Joy Fraser

Dr Fraser explains how Burns incredibly popular mock-heroic poem elevated haggis as a symbol of Scottish national identity.

The following years saw the haggis appear in several other poems throughout the 19th century and into the 20th century – with popular poets borrowing Burns’ language and imagery.

“Burns, inadvertently or not, created this image of haggis as being a typical Scottish peasant food,” Dr Fraser said.

“A poverty food, but a very different kind of poverty – it’s a nutritionally and morally robust kind of poverty food.

“And this becomes part of this whole sort of idealised image of the Scots as kind of resourceful, resilient and independent.”

Food writers then took up the idea of haggis as a traditional Scottish dish.

F Marian McNeill, in her book The Scots Kitchen, published in 1929, describes the haggis as “a testimony to the national gift of making the most of small means”.

So haggis, with its origins as a luxurious delicacy, becomes thought of as the embodiment of not letting anything go to waste.

After Burns died in 1796, a group of friends got together to celebrate his life and this was followed by “Burns Clubs” popping up in various places.

A tradition was formed and on Burns’ birthday, January 25, societies, clubs and groups of friends hold Burns Suppers across the world with a haggis as the centrepiece.

“These days it’s very much sort of reentered the realm of the every day for Scottish people where it is not really just a special occasion dish,” said Dr Fraser.

“You can just get it in the supermarket and there are all these different sorts of products,” – like your battered haggis, haggis pizza, and haggis pakora.

Dr Fraser’s paper, co-authored with Christine Knight, called Signifying Poverty, Class, and Nation through Scottish Foods: From Haggis to Deep-Fried Mars Bars, is featured in a recently published book The Emergence of National Food: The Dynamics of Food and Nationalism.

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country