D-Day veterans have shared their memories of war on the 80th anniversary of the landings at Normandy.

Allies left Portsmouth for the beaches of Normandy in France eight decades ago at the start of what was the largest seaborne invasion in history.

More than 150,000 Allied troops launched a massive beach assault on the coast of Normandy by air and sea, part of Allied plans to liberate German-occupied western Europe.

A total of 4,414 troops were killed and more than 5,000 wounded.

Veterans in Scotland have shared their stories of storming the beaches of coastal France, laying the foundations for the end of the Second World War.

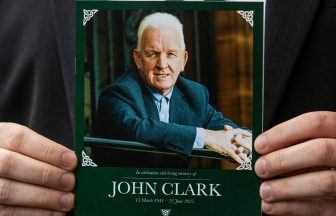

John: ‘There are some incidents you don’t forget’

John Mitchell will be 99 when he falls silent to remember his, and his comrades’, D-Day efforts.

Born in Ayrshire, John was sent to work in the lace trade in the town of Newmilns in 1938. At this point, John was only 14.

One year later, the lace factories were repurposed to contribute to the war efforts.

Specifically, John was involved in the production of sand fly and splinter netting, which was used to develop camouflage for soldiers at war.

As fighting scorched the earth of Europe, those on the home front, even at John’s tender age of 15, played a pivotal role in manufacturing essential items for frontline warfare.

But, with the knowledge that World War Two was not to be over in a jiffy, John and his young colleagues joined the Cadet Forces in the evenings.

John was specifically sent to the Air Cadets, where he learned about aircraft recognition and Morse code.

But as a teenager approaching adult status, John’s destiny was unelusive.

He said: “When you were approaching 18 years old, everyone was just waiting to be called up. For me it was on December 17 1942.

“It was then that I was off to the Army, where I completed basic training at the bitterly cold Bridge of Don Barracks in Aberdeen, which was followed by some aptitude tests. I then became Signalman John Mitchell of the Royal Signals.”

John’s first operational posting was to Weybridge in Surrey. Within a few days, John and his fellow Signallers headed south for the invasion build up, where they were “packed in camps.”

“Before I knew it, I was sitting on the cobbled slipway at Gosport on an LST, which had space for about 20 tanks and some smaller trucks, one of which I was in.

“These vessels had a speed of 13 knots and bobbed about like corks when at sea because of the shallow draught.”

What lay ahead was a revelation for those making the journey across the Channel.

John and his fellow troops knew they were at sea and had an idea they were heading to the French coast.

But such was the secrecy laden over Operation Overlord, it wasn’t until they were on their way to Normandy that they found out what they were about to do.

“When we were at sea, news came through about the landings and we knew for certain that this was not another exercise. It was the real thing.

“We landed on the night of D-Day plus one, on Juno Beach near Courselles. There have been many articles written about what we were to see on the beach with the noise of battle and all the bodies.

“I am sure that anyone who was there will have special memories of their own.”

For John, he believes that those who landed on D-Day, those involved in Operation Overlord, will have done their best to “eradicate these memories from their minds.”

He recalled a beachmaster who, through a megaphone, “shouted to everyone to get off the beach.” John did so, through a break in the wire which was marked with tape.

John was detached from most of his unit, so he advanced as far as he could in search of them.

But he was then told to stop, as was everyone else, unless they spoke fluent German.

At this point, John was static for hours, having to wait until the early morning of the next day to continue his advance.

As time began to blur, John began moving with a Canadian truck, but within a few moments, an eternal ghost was born for John.

He said: “The Canadian driver drove forward a couple of yards and hit a mine. The truck was destroyed.

“There are some incidents that you do not forget. We did our best to back out and eventually we found our unit.

“To start with, I was put onto a halftrack and on the radio set. I was working with two Battleships – the Ramilles and Warspite, I think – which were bombarding enemy strongpoints.

“It wasn’t long until I witnessed the effect of bombs having been dropped on a concentration of Germans trying to cross a river.”

Following Normandy, John made quick progress through sections of France – Caen, Yvetot, Le Havre – before moving on to Brussels in Belgium. Amongst many dark memories of the operation, John remembers Brussels fondly.

“We were given a great welcome, being showered with flowers, and given grapes, peaches, and pears. But Turnhout was a special place.

“I was invited into a house and made friends who seemed to accept me as part of their family. That friendship is still ongoing.

“Sixty years later, my wife and I managed to return, and when we did, we were honoured guests.”

Whilst John was in Belgium, he provided communications for an American Division which was going into action for the first time under the control of 1 British Corps.

This American Division was the 104th Infantry Division, known as the ‘Timberwolves.’

This led to a rapid deployment through European towns and cities.

John moved through Breda, Tilburg, Riel and Goirle. Whilst John progressed, the Germans were on their own violent manoeuvres.

John said: “I remember the Germans counterattacked in strength in the Ardennes and ran riot through the American lines. They were eventually beaten back and, before long, we were going into Germany.”

Many would ponder that the imminent end of a bloodied, feisty war, in which despair, violence, and irremovable images were emblazoned as eternal memories, would bring indefatigable joy. Alas, the reality was much different, as John explains.

“Duties became of a different nature. The aftermath of the liberation of Belsen was working its way through and the famous trials that followed commenced in September 1945.”

John remembers the part he played in this historic moment.

“We manned and operated the main telephone switchboard in Munster and were on detachment in Cologne on a wireless truck, on the esplanade next to the Rhine.

“The city was devastated with extensive ruins and blocked roads. I was amazed that the cathedral was so intact.”

John refused to feel settled as so often the Army were ready to pack him up and send him off to wherever action was occurring. This was a wise move.

Before long, John was shipped to the Middle East.

It was in the Middle East that John’s war would end. He spent time moving through locations once again, spending the largest proportion of his time in Gaza.

His memories here are grounded in two competing sentiments. First, the time wondering what they were doing there, as there seemed to be no war duties to fulfil.

As a result, John spent much of his time collecting dispatches from around the region. Second, he remembers when, for the second time, disaster tantalised him.

“We didn’t seem to have any military duties to perform and wondered why we were there at all. But it was a very dangerous place for British troops and my CO, for whom I acted as a driver on occasion, narrowly missed being blown up in the King David Hotel.”

Thankfully, nobody was injured. Now, return to the United Kingdom was imminent.

In 1947, John left the army. He returned to the lace trade and, over the subsequent years, worked hard to become a director in his trade.

He was ‘privileged’ to return to Normandy for the 60th anniversary of D-Day, which he described as “memorable and emotional.”

And, in 2015, he was “surprised” to receive word that, as a Normandy veteran, he was to receive the French Legion D’Honneur, which was first established by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1802. This award was to recognise his Service to France, our Auld Alliance remaining strong, firm, unbreakable.

Today, John resides in Galston, where he grew up, and hopes to attend any D-Day memorial he can to mark the 80th anniversary of the invasion that changed history.

Dr Claire Armstrong OBE, CEO of Legion Scotland, said “An imperishable thank you is owed to John, and so many more of his generation. John wasn’t just heroic during D-Day, but throughout the course of his generation’s war. We are proud to count John as a friend, and we will be dedicating a period of thanks, and a period of remembrance, in our hearts and minds on June 6, 80 years to the day since his participation in the D-Day landings.

“We must remember that whilst global history was changed by the actions of thousands of our bravest, so too was each of our lives. Without John, without those that did, or subsequently have, fallen, and without those who remain, none of us would be here, as we are, today.”

Cyril: ‘We were civilian kids with uniforms on’

Cyril “Dickie” Bird is 100, a recipient of the Military Medal and Legion D’Honneur, and an alumni of the 5th Royal Tank Regiment (5RTR). He lives in Edinburgh with his wife, Liz.

On June 6 1944, around midday, Cyril set sail for Gold Beach in Normandy. He did so as part of the Allied invasion of northern France, legendarily named the D-Day landings.

The landings remain the largest amphibious assault in military history. 175,000 troops stormed the beaches or landed behind enemy lines.

Such credentials don’t sit easily with Cyril, who was known as “Dickie” throughout the war due to his surname.

He said: “I was frightened, but I wouldn’t have missed it for the world. We were all aware that we were part of history and I kept going for my crew. We knew what we had to do.”

After the war, Cyril was told by an Army doctor, that he was ‘bomb happy’, which today would be diagnosed as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Cyril’s unit landed on Gold Beach at midday. In the morning, Royal Marine Commandos had broadly cleared the beaches. Cyril and his unit were joining the battle to provide heavy weaponry to the fight.

Gold Beach was one of five sites of the Allied invasion on D-Day. Targeting Gold and four other beaches, the Allied invasion sought to begin the pursuit to reclaim France.

D-Day eventually acted as the launch pad for the reclamation of Europe and subsequent victory on the May 8 1945, a date known as Victory in Europe (VE) Day.

But Normandy wasn’t the beginning of Cyril’s war. He had joined the Army in 1941.

His father, a career soldier, had falsified his birth certificate, and that of Cyril’s younger brother, Geoff, so that they could join the war effort before they were legally allowed to.

Cyril began Army life at the Armoured Fighting Vehicle School at Bovington in Dorset, where all tank crews are still trained. Six months later, following the completion of his training, Cyril was posted to 5RTR and soon set sail for Egypt, leaving port at Greenock.

It was here that Cyril joined the Desert Rats, an Allied fighting force in northern Africa.

Cyril and his 5RTR colleagues fought their Crusader Tanks and were present in battle for the first Allied victory over the Germans and Italians at the Battle of El Alamein.

The Battle of El Alamein, whilst in history a decisive victory that marked the end of Axis rule in Africa, was bloody. More than 23,000 troops were killed or wounded on both sides. But from there, it wasn’t long before Cyril’s war took him to Italy.

He fought through Salerno, ending up at the River Volterno, which lays at a midpoint between Rome and Naples. It was here that 5RTR, after a year and a half of fighting, were returned to the UK for some rest and recuperation.

Upon their return to the UK in December 1943, 5RTR were re-equipped with Comet tanks. They were based in Shakers Wood in Norfolk, which exists still as a military heritage site.

Whilst stationed here, Cyril went around England collecting new Comet tanks, and undertaking extensive training. They were still unsure as to where they would be going next, but it was clear that a momentum was beginning to build. In the minds of the boys of 5RTR, something was coming.

“We didn’t know where we were going next, but we knew that we wouldn’t be in Shakers Wood forever. There was talk of heading south to the coast to the port where vessels would depart, but the destination was all speculation.

“We spent a lot of time training, getting used to our new tanks, and as a driver I travelled around the country collecting them and bringing them to our unit. But there was some downtime too.”

Speculation soon gave way. On June 5, Cyril and his crew boarded a landing craft, launched in the Channel, and headed for Gold Beach, near Arromanches, in rough weather.

“We weren’t inside the tank. We were on the mess deck all the time. You only mounted the tank an hour or two before you landed. We made sure everything was working.

“I remember very clearly when we rolled off onto the beach. It was very frightening. But the tank worked beautifully.” Cyril then quipped, “regrettably”.

Many might imagine that driving a tank up a beach towards significant enemy resistance might require a focus on enemy location, and you’d be forgiven for picturing brute force, loud explosions, and an oily, smelly, claustrophobic cockpit. But Cyril dispels that myth.

“In an operation like that, you are focussed on communication. Communication with your crew, and with the squadron of tanks that you are advancing with.

“A fear is that our communications fail. I am proud to say that for the whole operation, our communications were immaculate.”

5RTR advanced through Gold Beach, leading the line behind Commandos from the Royal Marines.

On the first day of Operation Overlord, 10,000 Allied troops were injured. Cyril wasn’t one of them, but it wasn’t long before his time came.

Cyril was wounded in Normandy when a shell exploded in close proximity. Shrapnel lodged in his back, and in his legs. This forced Cyril’s return to the UK, where he was treated at Taunton military hospital, followed by a convalescent home in Bournemouth.

These were short stays, for Cyril rejoined his regiment three months later in Holland, and they soon liberated Ghent, a port city in Belgium with a population of 335,000 inhabitants.

This was shortly before Cyril’s involvement in the infamous Operation Market Garden, an airborne assault on Arnhem.

Cyril was wounded again, with shrapnel striking his jaw, resulting in a loss of some teeth. It was here that his Military Medal was won.

Cyril continued to fight through the rest of the war. He fought in Ardennes, which was dramatised in the globally successful Spielberg TV show Band of Brothers.

Following this, Cyril was involved in the liberation of Germany, and arrived in Hamburg on the May 8 1945, known as Victory in Europe Day. He remained in Germany for a year, returning home to the UK in October 1926.

But it is D-Day that he recalls most forthrightly. The comrades lost – he has visited all their gravesites across the world – and the fear he felt, the fear that’s never left.

“I suffer with anxiety neurosis. This was commonly called ‘being bomb scared’. I remember coming home and I would be at the cinema, or I’d be at home, and suddenly I’d be soaking wet, shaking with fear.

“I would think ‘what the hell is wrong with me?’, but I wasn’t the only one.

“After a day or two, or sometimes an hour or two, I find the beauty in this. Without speaking, we’d hold hands and know that…” Cyril stops speaking to gather himself.

Cyril’s wife, Liz, picks up and said: “He was very close with the other guys”, at which point Cyril twinkles, and reels off names of fallen comrades.

“Harry Bragg, Vick Vale, Roger Thrope, the guys who didn’t come back. We’ve been back to their graves.

“They were all kids. We were all kids. We were all civilian kids with uniforms on. I don’t think I am consciously proud of what we all did, but I am still proud of being a Desert Rat.

“We were the best Armoured Fighting Unit in the British Army, or any Army at that. We fought across Europe, right the way to Germany. We went all the way.”

Dr Claire Armstrong OBE, CEO of Legion Scotland, said: “Cyril Bird is a behemoth. I had to look this one up – not a word I would ever use so would be better to replace with a more familiar adjective; a gentleman. We are exceptionally proud to count him as a friend.

“Cyril has battled the consequences of war for eight decades, but, in his own words, he ‘wouldn’t have missed it for the world.’ That is a dedication to service that must receive an eternal thanks. His contribution to the future of Scotland, of the United Kingdom, and of Europe, is a contribution that we reflect on, and that we pay a boundless tribute to.

“We look forward to welcoming Cyril to the Usher Hall, with our partners at Poppyscotland, on the evening of June 6, where over 1,000 people will join together to pay tribute to his Service, and to the Service of his generation.”

Scotland’s Salute: A Tribute to D-Day 80 will take place at the Usher Hall in Edinburgh on Thursday June 6.

The concert will feature music from His Majesty’s Royal Marines Band Scotland and the Military Wives Choir.

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country