Len Murray, who has died aged 90, was one of the leading lawyers of his generation, was the first media spokesperson for the Law Society of Scotland, a much admired Burns scholar and one of the most stylish after dinner speakers at home and abroad.

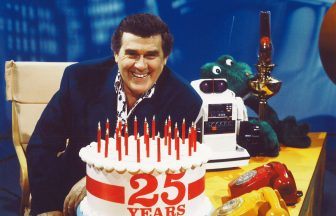

He had an association with the Glasgow firm of Levy and McRae for over 40 years. Like Laurence Dowdall, Ross Harper and Joe Beltrami, he featured regularly in the media owing to the high-profile nature of many of his cases.

Murray specialised in criminal law and was regarded by some colleagues as peerless in the matter of the cross examination of witnesses in criminal trials.

When he started out in the late 1950s, the circulation of national newspapers relied in part on “good” crime stories. As he became more prominent in the profession, he was sought out by journalists.

Back then, journalists and lawyers had a symbiotic relationship. Bits of information led to scoops and scoops led to some lawyers being minor public figures in their own right.

STV News

STV NewsOne of the closest personal and professional relationships Murray had, was with the then Scottish Daily Express journalist David Scott.

Scott would go on to be a senior journalist with the BBC before becoming controller of news and current affairs at STV. It was Scott that brought Levy and McRae to STV to legal stories.

The firms most difficult case was successfully defending an action by Antanas Gecas, who was exposed as a Nazi war criminal in an STV documentary fronted by Bob Tomlinson in 1986.

The programme paved the way for the War Crimes Act of 1991 and to Gecas’ humiliation when he lost a defamation action against STV at the Court of Session.

“I watched in awe as he commanded a courtroom with his eloquence and persuasive skills”

David McKie, Levy and McRae

Leonard George Murray was the youngest of five children. He hailed from the Knightswood area of Glasgow.

His father was the head teacher of a primary school. A love of learning, particularly the classics was a key characteristic of the household. Aged 14, he won an essay competition organised by the Hispanic Council of Great Britain.

In 1951, he went to Glasgow University to study modern languages. In his second year he was hit with a double setback. His father died and he contracted TB meningitis which involved a six month stay in Belvidere hospital.

On the upside, he was cared for by a fevers nurse at Belvidere. She would later become his wife.

He dropped out of university, but in 1954 started an apprenticeship in law which involved taking a degree. He graduated in 1957.

At the age of 27, Murray was indelibly affected when his client, 19-year-old Anthony Miller, was hanged in Barlinnie prison for the capital murder of a man in Glasgow’s Queens Park.

David Scott says that he remembers that Murray was ashen faced as he went down to the cells to speak with his client adding “he wanted to do more for Miller, and he carried the weight of the case for the rest of his life”.

Anthony Joseph Miller was hanged on December 22, 1960. Len Murray died 63 years to the day after the execution of his client.

The experience led to a subsequent hatred of the death penalty and decades later, Murray could be moved to tears when telling of the agony of Miller’s family as they campaigned for their son to escape the hangman.

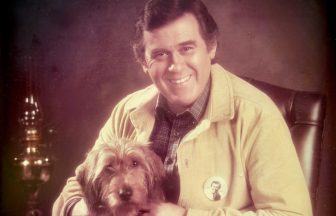

Murray was the one-time lawyer and campaigner for Paddy Meehan, who had been convicted of the murder of Rachel Ross in Ayr in 1969. The case was the crime cause celebre of the 1970s.

Meehan spent seven years, largely in solitary confinement, protesting his innocence and Murray along with Nicholas Fairbairn, Ludovic Kennedy, David Burnside and David Scott, campaigned to establish Meehan’s innocence. He was granted a Royal Pardon in 1976.

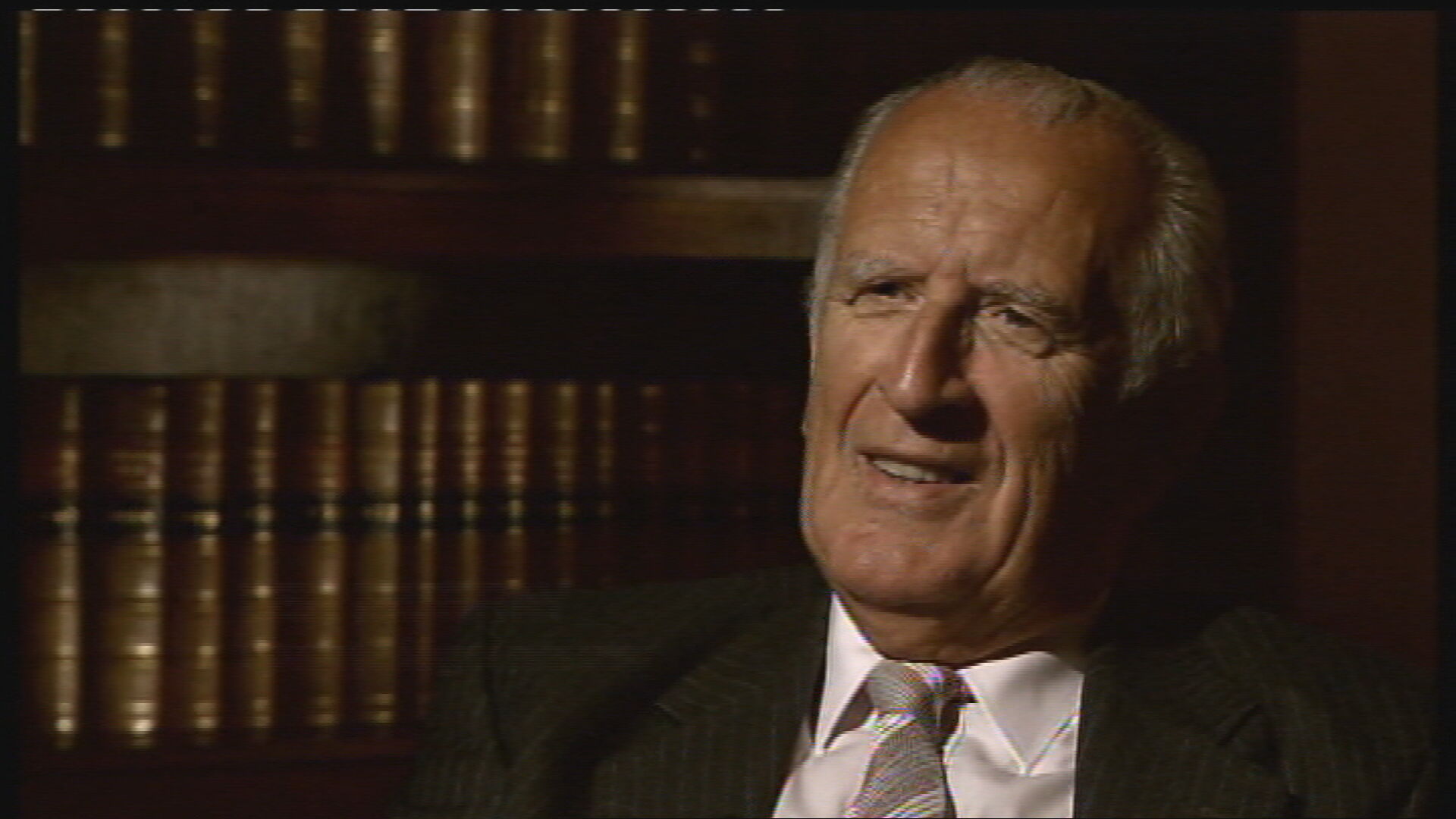

Described by a High Court judge as the finest pleader of his generation, Murray brought intellectual rigour, common sense and a stylish wit to his work. He carried himself with an air of natural authority which was buttressed by a distinctive voice which occasionally hinted at the theatrical.

His protege, and now senior partner at Levy and McRae, David McKie commented: “I watched in awe as he commanded a courtroom with his eloquence and persuasive skills.

“He was always at the end of the phone when I had a difficult legal call to make, when I was approving front pages of newspapers or the lead story on the news and his calm authority was a source of great reassurance to me.”

In 2002, he published a part memoir, part compendium of his celebrated cases in his book, The Pleader.

The Miller case haunts the text, which also contains the story of Freddie Cairns who was acquitted of the murder of another prisoner, Alexander Malcolmson, in Barlinnie prison in 1965.

Cairns then made a confession to David Scott that he had in fact murdered Malcolmson. The Scottish Daily Express had a scoop of historical proportions.

A public outcry ensued as Cairns could not be retried on the murder charge. He died before the Crown could prosecute him for perjury.

Peter Watson, who succeeded Murray as the senior partner at Levy and McRae said: “Len enjoyed a close working relationship with most senior members of the Scottish Bar who became judges.

“He was respected for his honesty, his integrity and the sense of humour which he used like a rapier to cut through any situation.”

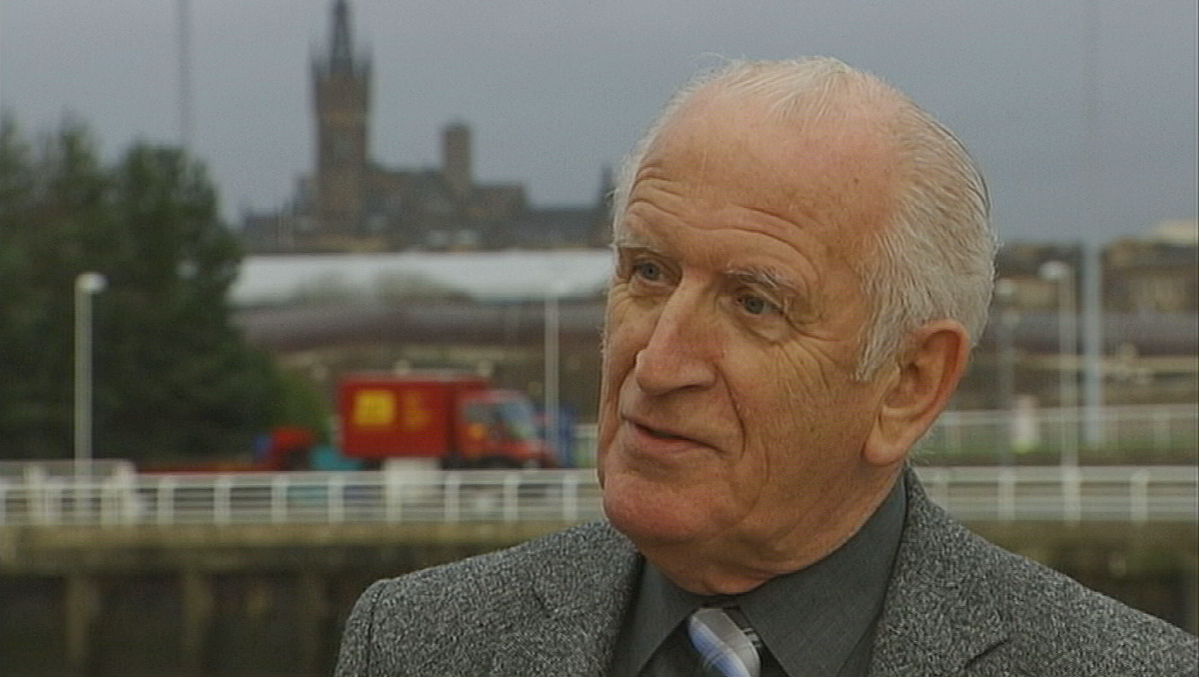

Murray was a natural story-teller, who could rely on perfect diction and a comic’s sense of timing in recounting whatever narrative.

It was no real surprise that when he fully retired in 2003, he went on to become one of the country’s most respected after dinner speakers. He could be funny without being “blue”.

He defined after dinner speaking as art and he would never cheapen that artform by seeking solace in tired routines or the recitation of jokes.

Murray had the distinction of being retained, at one time by both Celtic FC and Rangers FC although his loyalties and deep love was for Glasgow’s green and white.

He chaired testimonial committees for former players and was mooted as a possible club chairman when the family dynasties that controlled the club were forced out in 1994.

He was a sought after Burns speaker and travelled extensively to deliver immortal memories in five continents. He became the Dean of the Guild of Burns Speakers in 2019.

Len Murray delivered the best immortal memory I have ever heard. He entertained his audience with some light musings, before putting Burns in a worldwide literary context and marking some of his great works in the setting of momentous events in the eighteenth century.

His erudition was impressive and enhanced by a delivery that let his best observations hang in the air, to be savoured by his attentive audience.

Len Murray was a towering figure in legal circles and despite a distinguished career he rarely let it go to his head. He was an approachable man who had time for people, and he always carried himself with great grace and impeccable manners.

Lunch with Len was always a joy, the table being his stage and the food the intermission. Anecdote followed anecdote and started with the pre prandial Tio Pepe and continued long after the double espresso and armagnac had failed to quench the thirst for more.

He could be irascible when it came to mangled syntax. He would wear it as a badge of honour if I suggested he was the gestapo of the grammar police. Reporters using terms alien to the Scottish legal system was another bugbear and I daren’t report what he thought of the linguistic lows of ex-footballers as pundits.

For someone who started his working life to the thud of old typewriters, the smell of the inkwell and the dustiness of the manila folder, Len took to new technology when others of his generation dismissed it with a grunt and an impatient wave of the hand.

He had his own website, was a regular Facebook contributor and even delved into the sewer that is Twitter. I can hear him correcting me, “Bernard, it is now called X, I’m surprised you are not up to date my boy”.

He had a deep faith. He took his Catholicism seriously without ever embracing the dogmatic, whether it be in his own beliefs or the judgements he made of others.

That faith was tested when first, his wife Elizabeth died in 2005 at the age of 72 and then in 2020 he was emotionally floored by the death of his son Kenneth at the age of 61.

The tributes on his Facebook page are simply lovely, as a roll call of Who’s Who in Glasgow and beyond pay tribute. He would allow himself a bashful smile if could he read them. What he would be more impressed with is that the posts are almost all literate.

His son Brian said something worthy of his dad. He told me, “my dad lived a full and colourful life with his equally colourful friends. Please don’t mourn his loss but celebrate his life”.

For a man who had a serious illness in his relative youth, Len Murray lived a life of impressive longevity. His contributions to the law and to the study of Burns were significant and are rightly marked and remembered.

But to everyone who met him and counted him as a friend, it is not his career eminence they give thanks for, but for that precious, enthralling and wonderful thing called friendship.

Len Murray will be forever remembered by me, as the patron saint of friendship.

He is survived by sons Brian and Derek, by grandchildren Siobhan and Chris and by great grandchildren Ruaraidh and Ailish.

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country

STV News

STV News