On the death of most politicians, there is usually a truce in hostilities between the political parties. A sense of respect for loss, demotivates any instinct to continue the verbal sparring.

And so it was on Tuesday with the news that James Douglas-Hamilton, Baron Selkirk of Douglas, had died at the age of 81.

The warmth of the tributes that accompanied the news, reached across the political spectrum. All of them are genuine and none uttered out of dutiful respect.

The genuineness of affectionate words can be diluted on days like this; sometimes because those uttering them only knew the deceased fleetingly or out of convention that it is distasteful to speak indifferently of the dead.

The observations on James Douglas-Hamilton are testament to the esteem in which he was held. There was no need to issue warm words out of dutiful respect, these all came from the heart.

James was softly spoken. His words were often punctured by an impish smile. He was so ineffably polite that you imagined he slept in cotton wool.

The aristocratic demeanor and old-world manners, camouflaged a steely persona. He was quite happy for people to regard him as a soft touch, for he knew therein, lay a misjudgment.

Like George Younger, he smothered meetings with opponents in such reasonableness that it could seduce them into a false sense of security. It was only after he bid a trade union delegation a polite goodbye that they realised that they had achieved little.

Whoever said that the definition of a diplomat is someone who tells you to go to hell and you look forward to the trip, must have had James in mind.

Lord James Douglas-Hamilton was the second son of the fourteenth Duke of Hamilton. He served as the Member of Parliament for Edinburgh West from 1974 to 1997 and as a list MSP for the Lothians from 1999 to 2005.

His background was conventionally aristocratic. He was a page of honor at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953.

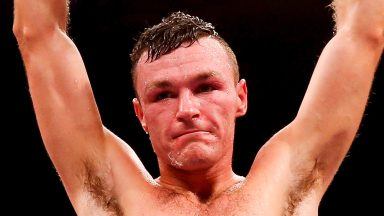

Eton, was followed by Balliol College Oxford, where he was president of the Conservative Association and the Oxford Union. Rather more improbably, given his gentle manner, he was also a boxing blue.

He was elected for Edinburgh West in October 1974. He held the seat comfortably in the Thatcher victory of 1979.

After the 1979 triumph, he served in the Whips office before becoming parliamentary private secretary to Malcolm Rifkind.

The Scottish Conservatives bore the brunt of voter anger as Margaret Thatcher became the Lefts bete noire.

The job of neutralizing the venom fell first to George Younger.

But by the time Rifkind became Scottish secretary in 1986 it was something of a lost cause. Home rule demands intensified as the party struggled to shake off an anti-Scottish image.

James Douglas-Hamilton served as a junior Scottish Office minister from 1987 before being made a Minster of State for Home Affairs and Health in 1995.

He was a slave to good manners and when he was assigned a female driver as a minister, he insisted on opening the car door for her. Among civil servants of the time, he was known simply as The Gent.

He was not overtly ideological. Something of a loyalist to the leadership, he was probably more instinctively of the One Nation tradition than the harder edge that Thatcher brought to government policy.

His devotion to the notion of public service meant that loyalty to party and country was more important than making a name for himself by rocking the boat. If he had misgivings about policy, they would have been expressed privately.

His public profile was high during the late 1980s and 1990s but not even his ameliorative air could save his party from being wiped out in Scotland in the Blair landslide of 1997.

In Edinburgh West he was under constant electoral bombardment from the Liberals (later Liberal Democrats). His majority fell to under 500 in 1983. The onslaught continued and he lost heavily to Donald Gorrie in 1997.

From Westminster he was elected to the Scottish Parliament in 1999 as a list MSP for Lothian.

Not noted as an orator or public speaker of any distinction, in many respects he shone in several contributions he would make in the new Parliament.

His House of Commons experience told in a Holyrood debating chamber that did not distinguish itself in the matter or oratory.

He would later become an active member of the House of Lords and was assiduous in attending to his Parliamentary responsibilities.

Like the late Tam Dalyell, the concept of the duty of a parliamentarian to serve people and country was keenly felt.

In some respect, he is a throwback, a reminder of the day when “proper toffs” were visible in Tory ranks. He also, as Lord Patten has said, is a reminder of how broad a church the Conservative party used to be.

Most tributes gush about his manners and rightly so.

A number of years ago, I was pitted against James in the annual golf match between Scottish Parliamentarians and journalists, a great charity event held that year at the splendid Roxburgh golf course.

He turned up with clubs with wooden shafts, a set of aristocratic hand-me-downs, probably gifted to a duke by an early titan of the game.

My golf was characteristically poor as I hacked grass so badly that the divots could pass as craters.

On the final hole I needed to make a nerve shredding four foot putt for a half.

I turned to James and gestured. “Oh yes dear boy, pick the ball up”. I halved the match courtesy of The Gent.

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country

Parliament UK

Parliament UK