Jamie Henry managed to spend a precious few hours outside hospital to celebrate his 27th birthday.

He enjoyed a trip to a restaurant with his family for a special occasion that was months in the making.

Jamie, who has autism and other complex needs, has been living in an intensive psychiatric unit at Woodland View Hospital in North Ayrshire for more than seven years despite doctors agreeing it is not suitable for him.

“He was all smiles as he walked into the restaurant and when he was sitting with us all,” said Sylvia McMahon, Jamie’s mum.

“It was just amazing to see his face. You could see that he loved it and I just wish I could get more of it. It’s destroying me because I know that’s what he needs.“

Support agencies say too many families of people with complex learning disabilities continue to feel powerless in a system that’s supposed to be helping them get their loved ones out of hospital.

Despite ambitious pledges and improvements in monitoring, groups claim real change has not happened, stripping those stuck in inappropriate care of their human rights and of what matters to them.

The Scottish Government say tackling this issue remains a priority, but Sylvia is calling for greater urgency in tackling the problem.

Sylvia said: “It’s so frustrating. I hate meetings. Meetings really break my heart because I’m telling them what Jamie’s saying to me.

“I’m telling them what I’m saying will help, and nobody’s listening to Jamie, and nobody’s listening to me.”

Two-and-a-half years ago, the Scottish Government set an ambitious target – to move a significant number of people out of inappropriate hospital stays by March 2024.

A national register was established in order to provide a fuller picture of those stuck in a similar situation to the one faced by Jamie.

“The shift that was expected to happen hasn’t happened,” said Alastair Minty, project coordinator with the charity In Control Scotland.

“Sadly because the power hasn’t shifted. The accountability still seems to be to the system, to the process; not to the individuals and the families for the continuing dire situation that people find themselves in.

“It’s really desperate. The stories that I hear regularly, they’re not just one-offs, that’s the problem.

“We can be thoughtful, we can be proactive, we can be responsible, but we can do that in a way that doesn’t deny people their human rights.

“A change of process is not enough. That shift of accountability, that shift of thinking, to stuff that we have known in the community for years has to happen. It has to happen in the hospital setting, as well as when somebody comes out.”

More than 1,400 people are on a dynamic support register.

Figures over the last year show some progress in tackling the numbers placed far from home but more are at risk of their support breaking down.

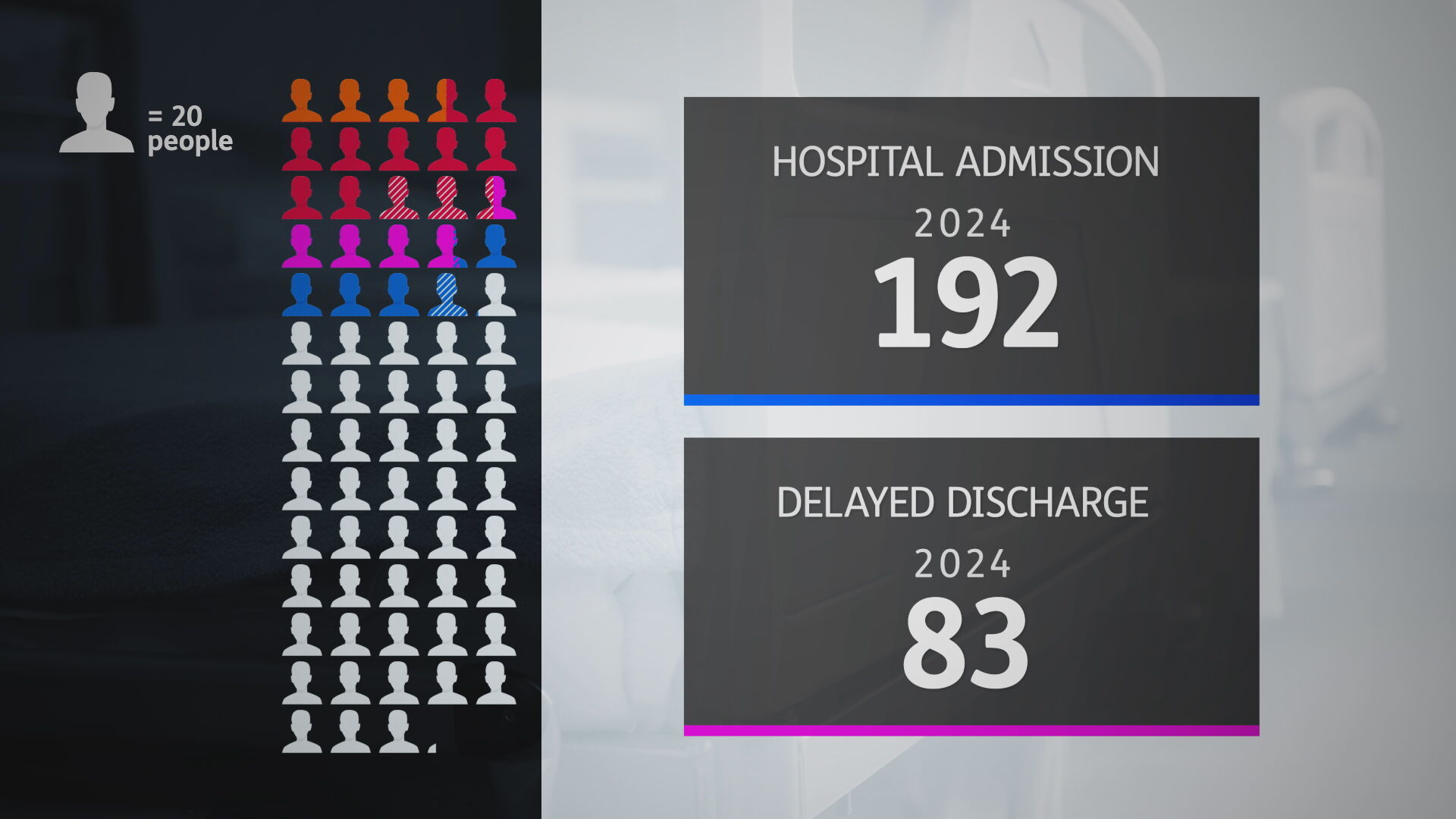

Of the 192 people in hospital, 83 were classified as a delayed discharge.

STV News

STV NewsDavid Jack, Fraser of Allander Institute, said: “We have over 50 adults who have been delayed for a year or more and some have been delayed for six years or more.

“What that data is telling us is the scale, the complexity and the urgency of the challenge. If you are going to classify data as urgent then we need to see progress.

“Delayed discharge could be for a number of reasons. It could be related to funding, accommodation or not having the appropriate care services available for those individuals.

“If we have people in hospital for as long as six years or more, you have to ask questions as to why that is the case if they are deemed suitable to leave the hospital setting.”

The Scottish Government say capacity issues and current pressures on social care have added to challenges.

Maree Todd, minister of social care and mental wellbeing, said: “If it were possible to fix this problem tomorrow we would have done it. So I guess the reality is – I am being absolutely honest and candid – there are a number of lines of activity that we are still pursuing.

“One of them is to try to ensure that local systems give this particular challenge a really high level of priority.”

The local authorities involved in Jamie’s care say its working collaboratively with his family, partner organisations and specialists to try to find the right community support.

Sylvia said: “I do see that things are moving and he will get out probably next year. But Jamie is seeing none of it.

“He has always been an outdoors boy and walking around the grounds is not what he needs. I don’t know what kind of boy I’m getting back out.“

Next month, a patient census will reveal the current numbers in institutional care.

Support agencies say progress is fragile and for those with more complex needs, it can feel like a long and torturous road back into the community.

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country