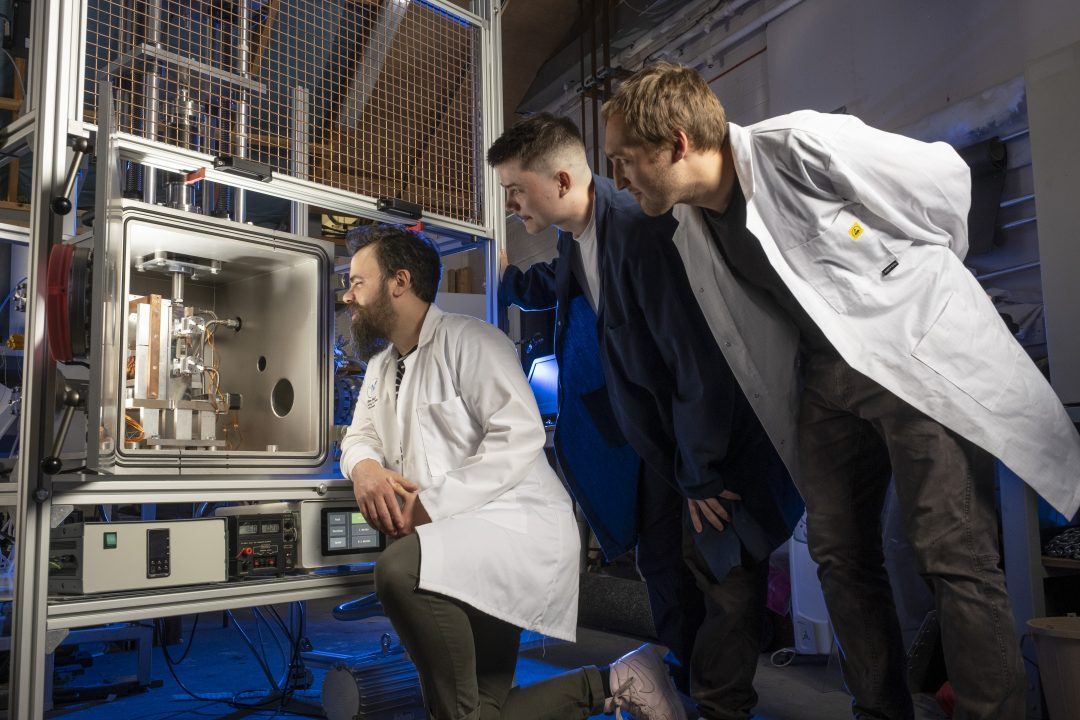

A small piece of outer space recreated in a basement in Glasgow could help future missions.

Researchers at the University of Glasgow’s James Watt School of Engineering have built the NextSpace Testrig – the world’s first dedicated facility for testing the structural integrity of materials that will be 3D printed in space.

The facility was developed by the university’s Dr Gilles Bailet in partnership with The Manufacturing Technology Centre, supported by £253,000 in funding from the UK Space Agency (UKSA).

It uses a specially-constructed vacuum chamber capable of generating temperatures between -150°C and +250°C to create space-like conditions on Earth, and is designed to help support the developing field of space manufacturing.

Space manufacturing aims to radically change how objects and materials are sent into orbit. Instead of carrying complete devices like solar reflectors into space on rockets, specially-designed 3D printers could create structures more cheaply directly in orbit instead.

Several experiments have already sent prototype 3D printers into orbit and metal parts have been 3D-printed by astronauts aboard the International Space Station.

Dr Bailet said: “3D printing is a very promising technology for allowing us to build very complex structures directly in orbit instead of taking them into space on rockets.

“It could enable us to create a wide variety of devices, from lightweight communications antennas to solar reflectors to structural parts of spacecraft or even human habitats for missions to the Moon and beyond.

“However, the potential also comes with significant risk, which will be magnified if efforts to start 3D printing in space are rushed out instead of being properly tested.

“Objects move very fast in orbit, and if a piece of a poorly-made structure breaks off it will end up circling the Earth with the velocity of a rifle bullet.

“If it hits another object like a satellite or a spacecraft, it could cause catastrophic damage, as well as increase the potential of cascading problems as debris from any collisions cause further damage to other objects.

Until now, no research facility has been dedicated to ensuring that polymers, ceramics and metals printed in orbit will be able to withstand the extreme physical strains they will face in space.

Objects in space are subjected to a hard vacuum that cycles rapidly between extremes of temperature – conditions that can wreak havoc on the structure of 3D-printed materials which aren’t rigorously constructed.

Imperfections such as tiny bubbles or poorly melted sections that might be inconsequential on Earth can behave differently in space.

Those flaws could cause 3D-printed objects to shatter, scattering dangerous fragments into orbit which would contribute to the growing problem of ‘space junk’ – pieces of debris from defunct satellites, previous space missions, or collisions between human-made objects in orbit.

The development of the NextSpace TestRig was supported by funding from the UK Space Agency’s Enabling Technology Programme.

Iain Hughes, head of the National Space Innovation Programme at the UK Space Agency said: “We are proud to have supported the University of Glasgow in developing the world’s first facility for testing 3D-printed materials in space-like conditions.

“This innovation will help to drive UK advancements in space manufacturing, unlocking numerous benefits and meeting the government’s growth ambitions while ensuring safe and sustainable space use.”

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country

University of Glasgow

University of Glasgow