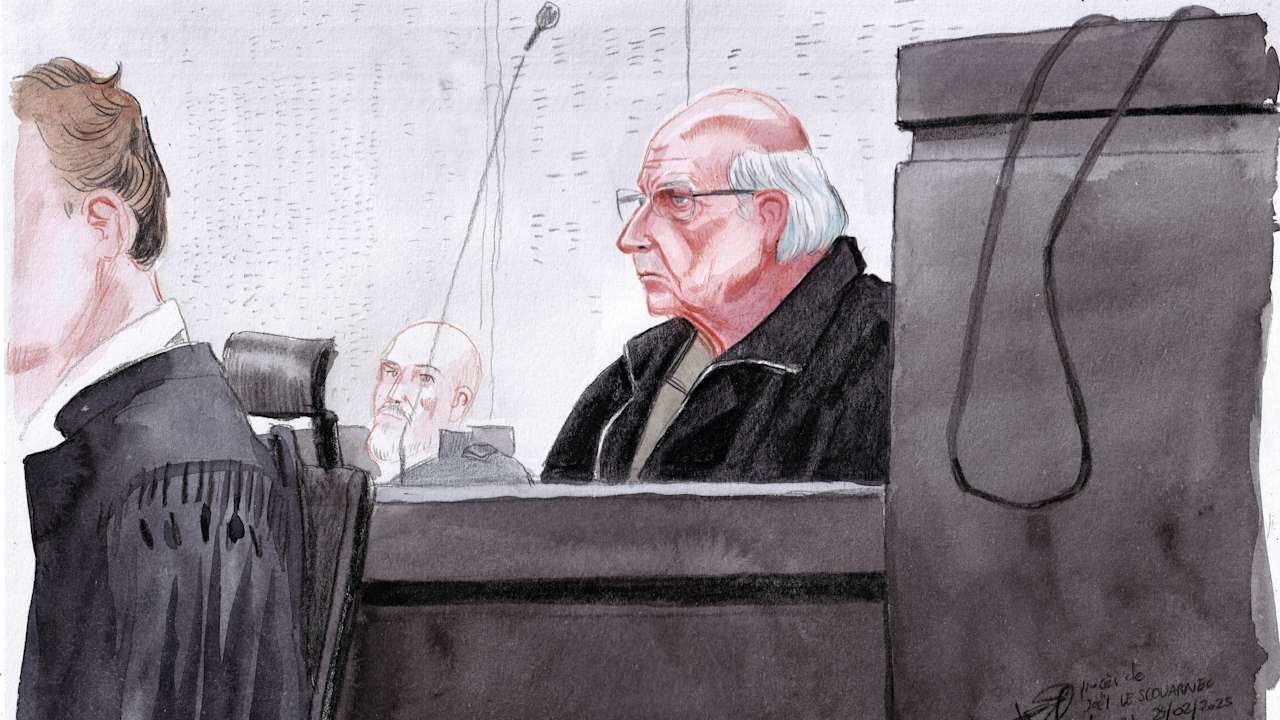

The final verdict in the trial of former surgeon Joel Le Scouarnec, who has admitted raping and sexually assaulting hundreds of child patients, is expected on Wednesday. His victims want to know why he wasn’t stopped sooner, as ITV News Reporter Sam Holder explains

Twenty years ago, Joël Le Scouarnec received a four-month suspended prison sentence for possessing child pornography.

Despite his conviction, the surgeon was allowed to continue treating children for more than a decade without any safeguarding measures put in place.

That conviction in 2005 should have been seen as a warning, but multiple French hospitals and medical centres continued to allow the convicted paedophile to have unrestricted access to children, including those under anaesthetic.

Now, after decades of abusing children, the trial of Le Scouarnec in northern France is nearing its end.

The 74-year-old has admitted to sexually assaulting 299 people, the vast majority of whom were children, during a 25 year period.

His victims expected this trial to be a watershed moment in France.

They expected it to dominate the headlines and lead to a national – even international reckoning – much like the recent case of Gisèle Pelicot, who was drugged and raped by her husband and dozens of other men.

But it has hardly had any impact at all.

“I’m not angry because rage doesn’t really help but I’m disappointed,” says Manon Lemoine, who has become a leader amongst the victims.

For years she had recurring nightmares following a hospital stay, but it was only when police knocked on her door in 2019 that she understood she had been sexually abused by Le Scouarnec.

“I’m disappointed with the media and with the politicians, who haven’t given a political response to this trial”, she told ITV News.

Manon and other victims wanted a special government commission – featuring the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Justice – to be set up in order to establish how Le Scouarnec was able to carry out assaults for so long and to work out why nobody stopped him.

They also want psychological and financial support offered to the victims, who were essentially left to fend for themselves after police turned up at their doors to inform them they had been assaulted as children.

Gabriel Trouvé, who was attacked when he went into hospital for hernia surgery as a five year-old, believes that the hospitals which employed Le Scouarnec bear responsibility, as does the justice system for not ensuring children were protected after his conviction.

“It’s a systemic problem,” he told me. “It’s a cultural problem too.”

Le Scouarnec seems to have been able to get jobs in hospitals and medical centres across hundreds of miles of northern France, in part, due to a shortage of surgeons in rural areas.

Hospitals, like the one he worked at in Jonzac, appeared grateful to have anyone filling the much-needed role and turned a blind eye to his criminal record.

At another hospital, a psychiatrist was tipped off about Le Scouarnec’s conviction and raised the alarm to hospital bosses, warning that he posed a threat to young patients, but they failed to take any meaningful action.

“What parent would ever imagine their child being abused when they go in for a surgical procedure,” said Regine, whose daughter was assaulted.

“[When I found out] the first thing I said to my daughter was sorry. Sorry for putting you into the hands of this predator. Sorry for trusting the doctors”.

She believes there has been an omèrta – a term for the code of silence used by the mafia – within medical institutions in France, in response to Le Scouarnec’s abuse, which is preventing lessons from being learnt and enables abusers.

Le Scouarnec kept detailed notes of all the assaults he carried out, which is how police identified many of the victims.

The notes, which form the backbone of the trial, were recovered during the investigation into a separate child sexual abuse case, for which he was convicted of assaulting four children.

Police found the files hidden under a mattress, along with hard disks containing 300,000 files of child abuse images.

Despite the number of victims in this case, the maximum sentence he can receive is 20 years in prison.

For many of those he assaulted, even more important than the sentence, is establishing how he was able to abuse for so long, at so many different hospitals and clinics, without ever being stopped.

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country