Today, at Manchester Crown Court, the harrowing statements from victims’ families were read to Mr Justice James Goss, whose job it was to jail Lucy Letby for a series of crimes that scope the depravity of the human condition.

For the unspeakable, she will spend the rest of her life in prison.

Let’s dispense with the normal clichés that often surround mass killers. Tabloid headlines scream about monsters, animals, angels of death.

Lucy Letby is not an animal or an angel of death.

What makes her crimes unfathomable is that she is a human being who has chosen to engage in mass murder in a way that takes the depravity of her actions beyond comprehension, if not rational explanation.

Police officers who interviewed her on arrest, talk of her matter-of-fact demeanour and the complete lack of empathy shown towards her victims.

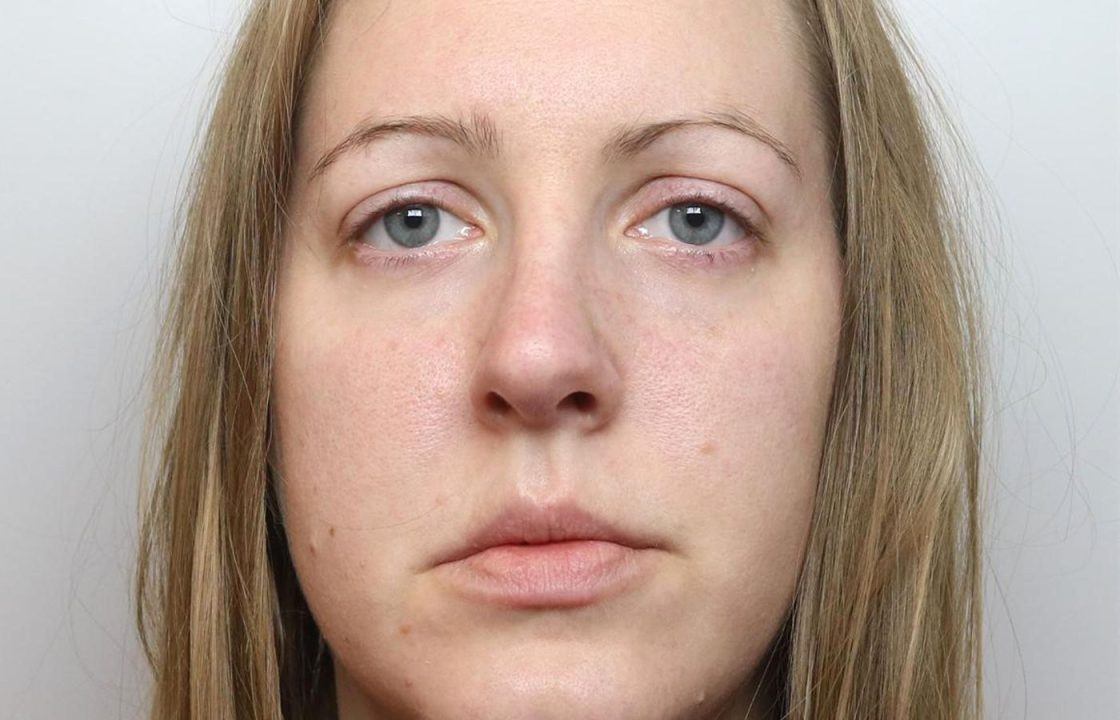

Pictures reveal an apparently happy young woman. There are no sinister poses, cold or dead eyes, which lead to questions about what trouble may lurk behind them.

In her appalling catalogue of premeditated killings, there is one question that a ten-month trial has not answered: Why did she do this?

Her parents must be anguished in trying to rationalise what drove an ostensibly normal girl to commit crimes that are almost incalculable in the hurt that they have caused.

She refused to turn up to Monday’s sentencing, adding another line to her infamy and sadistically further torturing the tortured.

The Prime Minister has said that legislation will be brought forward to compel those convicted to face the families of those on whom they have inflicted such appalling pain.

Some who count Lucy Letby as a friend simply cannot come to terms with the crimes that she has committed, with one telling the BBC’s Panorama programme that she did not believe Letby committed these crimes.

What that same programme also revealed is that there was a fundamental disconnect between senior clinicians and hospital bosses over concerns about the nurse.

What appears irrefutable, is that had she been removed from the care of children sooner, some of her victims would have lived.

It is hard not to conclude that senior managers were more interested in reputational management than actually listening to the concerns of staff. Not junior staff either, or nurses who were colleagues, but consultants who were perturbed by the levels of death and the fact that they all occurred when Lucy Letby was on the ward.

The inquiry that will probe these horrific events really has to be statutory in order that there is no wriggle room for people to evade its reach.

Now, the senior managers who did not act on consultant concerns may have a credible story to tell, for much of their apparent culpability is done from the perspective of hindsight. But they need to be compelled to attend and explain themselves.

I do not doubt that senior hospital managers grapple with many personnel issues in different parts of a hospital, all of which demand their time.

It is not unknown for some doctors to be assertive, even arrogant, and there is no doubt a danger that difficulties in relationships can cloud the interaction between doctor and manager in a way that loses sight of the central issue, which is putting patient welfare at the centre of everything.

Any inquiry will no doubt pour over every email and meeting that involved concerns about the nurse.

What is clear is that senior doctors had concerns and managers did not. Hindsight exonerates the former and indicts the latter, but it is for them to fully explain their actions or lack of them.

In the days following Letby’s conviction, I have watched a lot of interviews that talk of the “culture” within the NHS. It appears to be a set of behaviours that elevate protecting corporate reputation and individual positions above the need to dispassionately flush out attitudes or actions that harm patients.

The NHS is not unique in this. Almost any organisation with a huge remit, structure, and which is publicly financed, is compelled to have “governance” protocols to ensure “best practice”.

The problem with governance protocols is that they are easily ignored and even although there is an agreed position that “whistleblowers” should be heard, the experience of some who want to shine a light is that they are sent to outer darkness.

We should not be pretending that having an open culture is easy, since being frank and honest assumes that at some stage someone in authority might have to go against the grain and admit that wrong-doing occurred on their watch.

From the horrors of the Letby case must come a series of recommendations that impose on those in authority an absolute duty to genuinely put patients first, rather than playing with words that suggest transparency when actions suggest the exact opposite is the case.

Babies have been killed and their loved ones have been left to get on with a life that can never be the same again. The emotional consequences of the bereaved constitute a level of hurt that will never leave them.

Those with shattered lives will have asked themselves a million times: Why?

As Mr Justice Goss made clear it is not part of his function to ascribe motive. Only Letby knows why she did what she did.

She has proved adept in the black art of manipulation. Unless she breaks with habit, she will ensure that silence adds to her notoriety.

She will have plenty of time for silence. Home for the rest of her life is a prison cell. It will be her place of death.

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country

Cheshire Constabulary

Cheshire Constabulary