Words by Paul Tyson, Senior News Editor.

Afghanistan, 2007. British soldiers wait to enter a suspected Taliban compound somewhere in Helmand Province. Fingers in their ears they brace for the explosion that will blow a hole in the wall. The charge detonates and just for a moment one of the soldiers appears to light up as the dust blown from his helmet catches the early morning sun.

This is a rare glimpse of primary blast wave, a rapid pulse of energy that flies outward in all directions from the seat of an explosion, faster than the speed of sound. The soldiers in the footage don’t know it but scientists are increasingly sure that repeated exposure to this type of low-level blast is causing serious brain damage.

Helmets designed to stop bullets and shrapnel offer little protection against primary blast waves which send a rapid pulse of overpressure through the brain causing microscopic damage to blood vessels and cells.

Clara Limbaeck is a Consultant Neuropathologist at Oxford University Hospitals Trust: “There is more and more evidence that even a moderate injury can actually cause long term changes in the brain. And this also can be seen morphologically under the microscope. The danger of repetitive trauma is that often it can be quite mild, it can even be completely asymptomatic.

“You’re exposed to minor hits or minor pressure waves and you think that everything is fine but wide repetition of this trauma over time, it can have a profound effect on the brain,” she said.

If you’ve been affected by the issues in this article and would like to share your experience, email: investigations@itv.com

Today a leading head injury charity is calling on British military veterans to donate their brains for scientific research into the effects of blast. The Concussion Legacy Foundation says thousands of veterans may be suffering from Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) due to blast exposure during their service but the exact scale of the problem is unknown as the condition can be hard to diagnose.

Symptoms include memory loss, dizziness, inability to concentrate, sleep problems, mood swings and headaches. These may emerge years after the blast exposure that caused them and they overlap the symptoms of a psychological condition, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), to a large degree – add a lack of knowledge about TBI among healthcare providers and misdiagnosis is common.

Even acute TBI caused by a single major blast or repeated blasts in a short space of time often goes without diagnosis leaving soldiers suffering invisible wounds long after their service has ended.

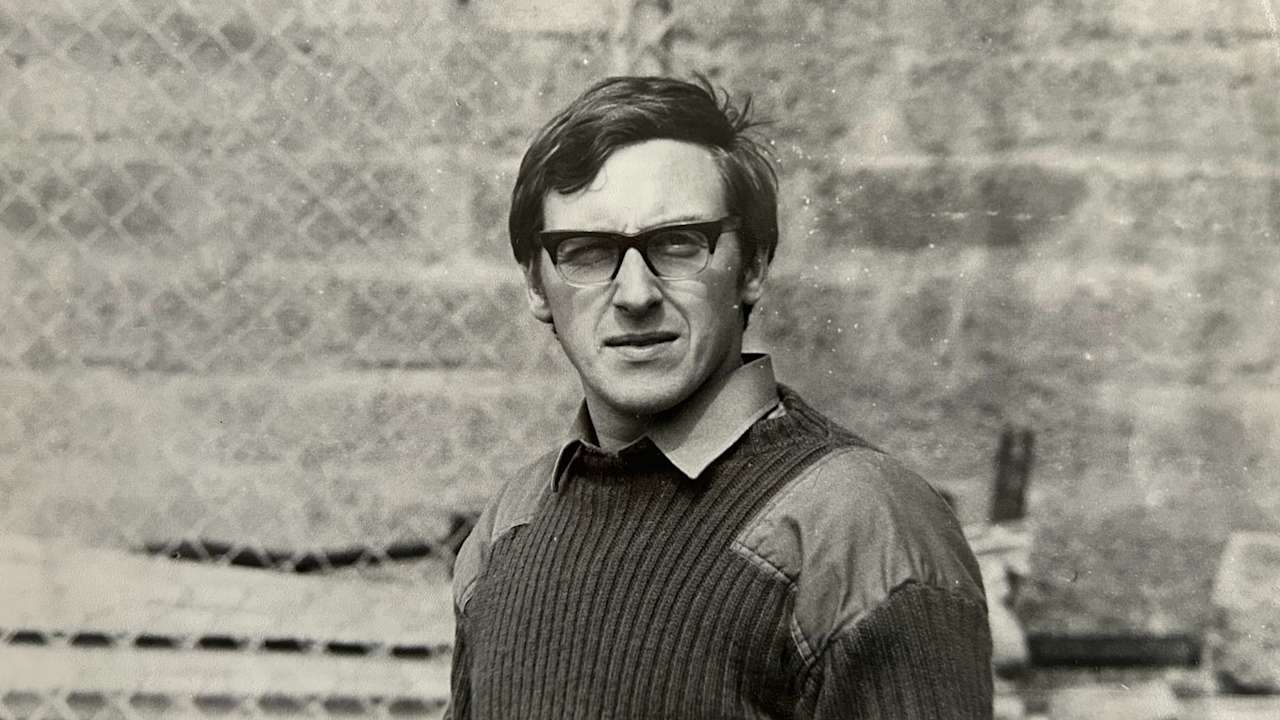

Tom Clarke served several tours of Northern Ireland before, in 1976, he was caught in an IRA mortar attack on his base in Crossmaglen, South Armagh.

“It was a massive explosion, my rifle got blown out of my hand. It feels as if every organ in your body is trying to escape it, trying to get out of your body. It’s a horrible feeling, it’s very difficult to explain” he recalls.

His visible injuries were minor and he was back on duty straight away but he knew something was wrong.

“For weeks and weeks afterwards I kept having these massive headaches and from then for about a year afterwards I don’t know it just became a blank to me. My wife said I started drinking heavily, started being argumentative, she said I was a holy horror.”

When Tom reported his symptoms to medics he was told to “lie down in a dark room.” It was only when an understanding officer noticed Tom’s decline and arranged for him to be posted to a unit in Germany where he worked with dogs and horses that he began to find peace.

The first Tom heard of blast TBI was when he saw an earlier report on ITV News a few weeks ago, recognised the symptoms and got in touch.

While there is no cure for blast TBI the symptoms can be managed and there may be a range of therapies that help but much about the condition remains unknown: Is there a safe level of blast overpressure? Could diagnosis be improved by using bio-markers or modern neuro-imaging techniques? What protection for the brain could be developed?

This is where well-funded discovery science is urgently needed. Gabriele De Luca, Professor of Neurology and Experimental Neuropathology at Oxford University runs a brain bank which is part-funded by the Concussion Legacy Foundation and includes several veteran’s brains. UK. He says the more material they have to study the more scientists can learn about the problem.

“Brain donation is a powerful gift. It’s a legacy. It allows individuals who have suffered during life to essentially continue our understanding of these conditions, for which at the moment, the recognition of the total extent, the severity, the nature of it remains suboptimal, and knowing that that can contribute to advancing our understanding, to help people in the future.

“Donating brain tissue in any circumstance in which there is a question about symptoms that relate to how the brain functions during life adds value to our understanding of fundamental biological processes. Now the complexity of blast injuries is that these often happen in individuals who are young, they’re athletic, and they engage in activities that may expose them to other types of traumatic brain injury, repetitive head impacts with sport for example, that make things even more complex, so understanding the full spectrum of exposures and then seeing changes that can only be discerned after life under a microscope is key to advancing our knowledge.

“And that knowledge will be important for us to understand, well, who’s at risk? What are the actual mechanisms by which that damage occur, are there things that we can do in terms of the damage getting worse or spreading? And importantly, what is it that we can do to reduce the risk and ultimately prevent these injuries from happening in the first place?”

Find more information at:

And if you’ve been affected by the issues discussed here contact Samaritans for help and support

Call: 116 123

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country