From the moment you enter the arrivals hall at Istanbul airport, you are greeted by giant screens and picture-perfect posters advertising cosmetic surgery.

There are slick airport lounges, but not the kind that serve an all-you-can-eat fry-up and mimosa.

Nurses and doctors tend to patients, rather than patrons, helping with their bandages, drains and post-surgical needs. You can be off a plane and checking into a hospital or hotel to be prepped for surgery within a matter of hours.

Bloody bandages, nose splints and black umbrellas to shade sensitive scalps from the blistering 38C sun are commonplace in the restaurants and shopping districts.

Signs of the local economy’s biggest money-maker are everywhere. Last year, more than one million people travelled to Türkiye as medical tourists and that figure is expected to double this year.

STV News

STV NewsThe marketing is mostly done online and is very glamorous. Scrolling through TikTok, you’re bombarded with – mostly paid for adverts – of young men and women telling positive stories about their procedures in Türkiye. The relatively-cheap cost and prospect of a poolside recovery are huge selling points.

As part of STV’s Scotland Tonight investigation, Glasgow woman Zara Janjua gave us exclusive access to follow her journey to Istanbul for a tummy tuck.

Zara is a recognisable face in the Scottish media landscape. Having interviewed and spoken to many people who have gone to Türkiye for surgery – with both good and bad outcomes – Zara struck me as someone who had really done their research into what’s involved with a tummy tuck, as well as insight into her chosen hospital.

STV News

STV NewsThe Acibadem Ataşehir Hospital boasts valet parking, spotlessly-clean revolving doors and floral displays at the reception desk to rival five-star hotels.

There’s no sign of the hardback NHS waiting room chairs either. Plush armchairs and sofas await patients, while a self-playing piano sits neatly in the corner. It was unlike any hospital I had ever been in before.

As we made our way up to one of top floors of the hospital, we met Zara’s surgeon, Professor Dr. Bülent Saçak. He was keen to impress the importance of face-to-face consultations with international patients.

He also expressed sadness over Türkiye’s reputation for botched surgery, particularly that his patients couldn’t stay longer to receive more aftercare.

Of course, more time on a ward comes at an extra cost.

On the morning of the surgery, Zara is much calmer than I expected. As the team runs through the procedure with her, we have a quick chat about what she’s getting herself into. She’s anxious but ready. I head into the basement of the hospital to scrub up and meet Prof. Dr. Saçak.

After a joke that he’s welcoming me into his natural habitat, he shows me around the state-of-the art facility. The hospital is less than a year old, delayed slightly by Covid.

STV News

STV NewsAs we walk around the surgical suites, I see people waking from the haze of anaesthesia and surgeons operating on patients.

Prof. Dr. Saçak shows me his favourite thing in the staff room – two giant full body massage chairs.

As Zara is wheeled into the operating theatre, the room is filled with hushed chatter, beeping heart monitors and Turkish music playing more loudly than expected from an integrated set of speakers.

Prof. Dr. Saçak has a dedicated team of nurses and assistants around him. He tells me, while he begins to prep Zara’s stomach, that he expects the surgery to take around four to four-and-a-half hours.

A tummy tuck involves making a 25cm cut in Zara’s tummy and stitching it back up again. After a week in the hospital, Zara is moved to a hotel in order to recover.

STV News

STV NewsWe’ve long flown back to Scotland by this point but her recovery has been on my mind.

When we meet again a month later, she is in great spirits and is very happy with her results. She tells me she’s been in regular contact with Prof. Dr. Saçak, a level of aftercare many who fly to Türkiye for surgery don’t get.

Even though her research was thorough and in depth, I’m left with the impression she wasn’t prepared for just how traumatic the surgery would be, or the physical toll it would take on her body. Her procedure was equivalent to two caesarean sections at once.

This has been a life-altering experience for Zara and an eye-opening one for me. So many Scots are taking the risk, despite the warnings, to travel for medical and cosmetic procedures. Not everyone has a positive experience like Zara, with dedicated aftercare and a long stay in Türkiye.

Just a week after our experience in Istanbul, I met a woman we’re calling Claire.

Claire did not have a dreamy, shiny experience.

STV News

STV NewsThe luxury hotel and hospital weren’t anything like the adverts on social media and after waking up from her surgeries, she described the nightmare situation of being left with a botched body. The damage to her mental health will take much longer than her scars to heal.

For those who chose to travel abroad and ignore the warnings, sometimes the price of perfection comes at a much greater cost.

STV News

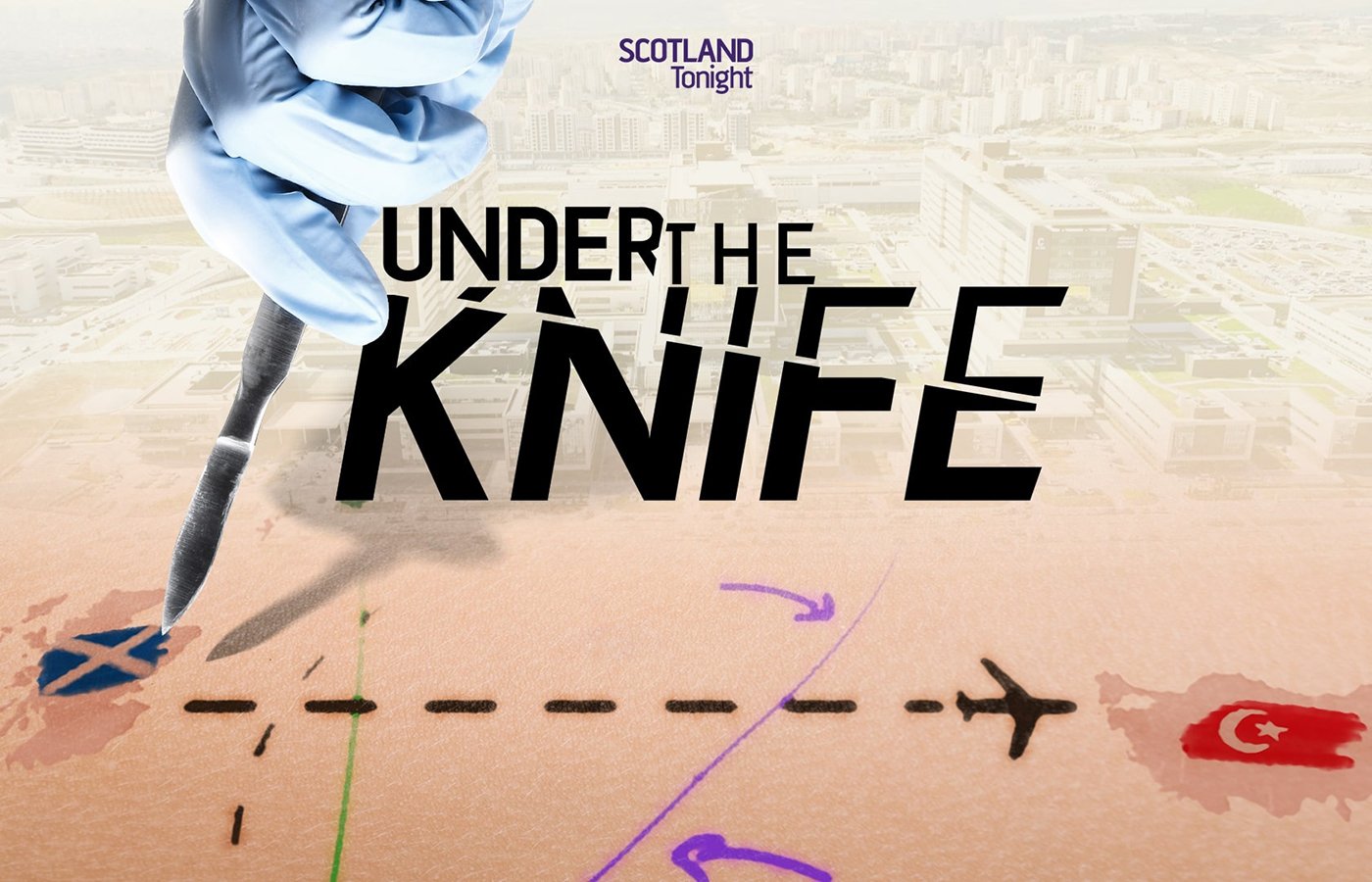

STV NewsFor more, including interviews with those who have lost loved ones to surgery in Türkiye, tune into Scotland Tonight’s ‘Under The Knife’ special series on STV Player.

Follow STV News on WhatsApp

Scan the QR code on your mobile device for all the latest news from around the country